By Basil Arnould Price

Translations are the author’s own.

On May 25, 2022, software engineer Helen Staniland streamed an interview with journalist Helen Joyce. During the interview, Joyce remarked:

“…we have to try to limit the harm and that means reducing or keeping down the number of people who transition. That’s for two reasons – one of them is that every one of those people is a person who’s been damaged. But the second one is every one of those people is basically, you know, a huge problem to a sane world. […] if you’ve got people who’ve dissociated from their sex in some way, every one of those people is someone who needs special accommodation in a sane world where we re-acknowledge the truth of sex […] So the fewer of those [transgender] people there are, the better, in the sane world that I hope we’ll reach.”[1]

Stanilard responded with a series of exaggerated nods.

Both women identify as ‘gender-critical’ feminists. ‘Gender-critical’ feminism is a movement that, as outlined by Holly Lawford-Smith in her new monograph Gender Critical Feminism (Oxford University Press, 2022), disregards the self-defined gender of transgender people (and trans women in particular), insisting instead upon the significance of biological, binary sex.[2] For ‘gender-critical’ feminists, being transgender is either buying into a ‘fad’ or the result of a ‘contagion’, ‘craze’, or ‘cult’.[3] This movement sees transgender people and trans-inclusive practices or policies as a threat to the concepts of ‘male’ and ‘female’ – or, as Lawford-Smith argues, to ‘feminism’ itself.[4] To respond to this unfounded threat, ‘gender-critical’ feminists advocate for excluding transgender people from single-gender spaces[5] or for limiting access to life-affirming healthcare. Although some authors within the movement, such as Holly Lawford-Smith, Kathleen Stock, and Abigail Schrier, denounce transphobia in their writings, these disclaimers neither erase nor excuse the authors’ dismissal of transgender identity, their claims of the danger transgender people pose to themselves and others, or, indeed, their longing for a world where transgender people do not exist.

This essay does not seek to explain the rise of modern gender critical feminism. Nor does it seek to dismantle the arguments of gender-critical feminists by demonstrating their errors or inconsistencies. This is partially because other activists and scholars have done this work[6], but also because anti-gender movements such as ‘gender-critical’ feminism do not have a clear doctrine. Instead, as foundational gender theorist Judith Butler observes in their recent essay for The Guardian, these movements “[mobilize] a range of rhetorical strategies from across the political spectrum to maximize the fear of infiltration and destruction […][the anti-gender movement] does not strive for consistency, for its incoherence is part of its power”.[7]

What I want to do in this essay is return to Joyce’s desire for a ‘sane world’. When I came upon Joyce’s comments, I wondered why a world without transgender people would be ‘sane’ and why anybody would hope for such a world. Being transgender informs this reaction, naturally, but so does my current research project on utopia in later medieval Iceland.

Medieval Iceland seems, at least at first, to be the ‘sane world’ that Joyce longs for. Medieval Icelandic laws attempt to circumvent gender nonconformity. The twelfth-century Icelandic law-code Grágás, for example, sanctions “lethal revenge for the mere insinuation of effeminacy.”[8] The laws threaten outlawry for insults – called níð or ýki – that accuse somebody of ergi: a term denoting gender nonconformance; non heteronormative sexual acts; and, specifically, a receptivity to penetrative anal sex.[9] The severe punishments for accusing somebody of ergi suggest that premodern Icelanders saw the behaviours that these insults allege as highly objectionable. Grágás further espouses gender conformity by punishing both men who wear women’s clothing and women who wear men’s clothing or adopt ‘any manly habits’[10] with lesser outlawry: a temporary but potentially lethal sentence.[11] Grágás appears to prioritise the ‘truth of sex’ and, even if these laws were not enforced, the thirteenth to fifteenth century Íslendingasögur (Icelandic family sagas) indicate that these stipulations were at least self-policed.[12]

And yet, the Íslendingasögur may also yearn for an escape from this supposedly ‘sane’ world. My contribution to my forthcoming co-edited volume, Medieval Mobilities: Gendered Bodies, Spaces, and Movements (New York: Palgrave, forthcoming)attends to two moments where the late medieval Króka-Refs Saga and Flóamanna Saga seem to desire and envision alternatives to these aspects of medieval Icelandic society by locating Greenland as a site of possible freedom from proscriptive gendered norms.

In Króka-Refs Saga, men claim that Refr settled in Greenland after he was sent away from Iceland because of his ergi..[13] These remarks insinuate that even if Iceland does not tolerate the bodies and behaviours associated with ergi, Greenland does. The saga stresses that these allegations are baseless – but nevertheless, points to Greenland as a possible destination for bodies and behaviours that do not fit within medieval Icelandic sexual and gender norms.[14]

However, the roughly contemporaneous Flóamanna Saga imagines Greenland as a location where gendered categories are genuinely defied. The saga focuses on Þorgils Ørrabeinsfóstri, who settles in Greenland with his wife Þórey. He soon finds his wife dead, and his infant son sucking uselessly at her breast. With no other way to feed his son, Þorgils cuts his nipples to nurse him. Another settler quickly slanders Þorgils, marvelling that he cannot tell ‘whether he is either a man or a woman’.[15] Unlike the remarks in Króka Refs Saga, this níð seems to point to a genuinely queer gender performance.

Some scholars have argued that Þorgils’s lactation reflects medieval humoural science or an awareness of the actual phenomenon of spontaneous male lactation in times of crisis. Such readings ignore that Þorgils actively induces his lactation.[16] Þorgils’s body perhaps could always produce milk — he only needed to make the choice to do so. On one hand, Greenland’s harsh climate and the impossibility of feeding his son otherwise may necessitate such a decision, whereas Iceland’s environment does not. But on the other, it may also have been unthinkable for Þorgils to induce lactation in Iceland, given the model of normative masculinity that is internalized and self-enforced by male characters within the sagas.[17] Greenland, perhaps, makes such an action thinkable.

I see this act as a particularly trans gesture towards the possibility of another world – but not the ‘sane world’ that Joyce seeks. In her interview and in her monograph, Trans: When Ideology Meets Reality (London: Oneworld Publications, 2021), Joyce positions ‘transgender’ as emphatically not ‘reality’, making, as queer theorist Sara Ahmed argues in a recent blogpost, a typically conservative appeal to ‘common sense’: weaponising ‘reality’: “[…] [in] an effort to restore racial as well as gendered hierarchies”.[18] Back to my initial question – why would anybody want reality? Þorgils sees that reality is, to paraphrase the late, great queer theorist José Esteban Munoz (2009), not enough.[19] By cutting his nipples, Þorgils refuses the inevitability of his son’s death, rejecting not just normative expectations of gender but also the narrowness of ‘reality’ itself to secure a more desirable future where both he and his son can live.

For transgender people, defying reality may be a survival strategy. Across the United States, where I am from, there has been a surge of legislation targeting transgender people, either by limiting or criminalizing healthcare, barring access to single-gender facilities, restricting opportunities for transgender students to participate in school or sport, and otherwise making even more challenging to obtain legal documentation recognising their name and gender.[20] In the United Kingdom, where I live, the systematic defunding of the National Health Service (NHS) and the multi-year waiting times for receiving trans-affirming healthcare pose a tangible threat to transgender lives.[21] Although my present is not analogous with medieval Iceland, in Króka Refs Saga and Flóamanna Saga, I nevertheless see a recognition of a violent and intolerant present but also a longing for something and somewhere else: a world outside of conventional gendered norms and the discourses that attempt to enforce them. For transgender people, as for Þorgils, there is no choice but to refuse a ‘sane world’ that wants you gone.

Basil Arnould Price is a Wolfson Scholar in the Centre for Medieval Studies at the University of York. He is the co-editor of Medieval Mobilities: Gendered Bodies, Spaces, and Movements, which will appear from Palgrave Macmillan in Fall 2022. His Ph.D thesis, tentatively entitled ‘The Shadow Age: Genre and Place in the Post-Classical Íslendingasögur,’ brings the spaces of the fourteenth and fifteenth-century Old Norse-Icelandic sagas into dialogue with postcolonial and queer theories.

Bibliography

Ahmed, Sara. “Gender Critical = Gender Conservative.” Feministkilljoys (blog), October 31, 2021, https://feministkilljoys.com/2021/10/31/gender-critical-gender-conservative/.

Ármann Jakobsson. “The Trollish Acts of Þorgrímr the Witch.” Saga-book 32 (2008): 36–68.

Butler, Judith. “Why Is the Idea of ‘Gender’ Provoking Backlash the World over?” The Guardian, October 23, 2021, https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/commentisfree/2021/oct/23/judith-butler-gender-ideology-backlash.

Ellis, Sonja J., Louis Bailey, and Jay McNeil. “Trans People’s Experiences of Mental Health and Gender Identity Services: A UK Study.” Journal of Gay & Lesbian Mental Health 19, no. 1 (2015): 4–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/19359705.2014.960990.

doi:10.1080/19359705.2014.960990.

Evans, Gareth Lloyd. Men and Masculinities in the Sagas of Icelanders. Oxford University Press, 2019.

Faye, Shon. The Transgender Issue: An Argument for Justice. Bristol: Allen Lane, 2021.

Jóhannes Halldórsson, ed. Kjalnesinga Saga, Vol. XIV. Íslenzk fornrit. Reykjavík: Hið Íslenzka Fornritfélag, 1991.

Joyce, Helen. Trans: When Ideology Meets Reality. London: Oneworld Publications, 2022.

Lassen, Annette. “Perseverance and Purity in Flóamanna Saga.” The Journal of English and Germanic Philology 118.3 (2019): 313–28. https://doi.org/10.5406/jenglgermphil.118.3.0313.

Lawford-Smith, Holly. Gender-Critical Feminism. Oxford University Press, 2022.

Muñoz, Jóse Esteban. Cruising Utopia: The Then and There of Queer Futurity. New York: New York University Press, 2009

Price, Basil A., Jane Bonsall and Meagan Khoury eds. Medieval Mobilities: Gendered Bodies, Spaces, and Movements in the Middle Ages. New York: Palgrave. Forthcoming.

Schrier, Abigail. Irreversible Damage: The Transgender Craze Seducing Our Daughters. Regnery Publishing, 2020.

Staniland, Helen, and Helen Joyce. “Wine with Women Ep. 4: Helen Joyce.” Podcast. Youtube, 5 Mar. 2022, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8_u1MQFjxvI.

Sørensen, Preben Meulengracht. The Unmanly Man: Concepts of Sexual Defamation in Early Northern Society. trans. Joan Turville-Petre, Odense University Press, 1983.

Þórhallur Vilmundarson and Bjarni Vilhjálmsson, eds. Harðar Saga. Vol. XIII. Íslenzk Fornrit. Reykjavík: Hið Íslenzka Fornritfélag, 1991.

Finsen, Vilhjálmur, ed. Grágás: Efter Det Arnamagnæanske Haandskrift Nr. 334 fol., Stadarhólsbók. København: Gyldendal, 1879.

— ed. Grágás: Islændernes Lovbog i Fristatens Tid, Udgivet Efter Det Kongelige Biblioteks Haandskrift. 2. Vol. 2. København: Brødrene Berlings Bogtrykkeri, 1850.

Zanghellini, Aleardo. “Philosophical Problems with the Gender-Critical Feminist Argument against Trans Inclusion.” SAGE Open 10.2 (2020): https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244020927029.

[1] Helen Staniland and Helen Joyce, “Wine with Women Ep. 4: Helen Joyce.” March 5, 2022, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8_u1MQFjxvI, 4:48-5:38.

[2] Holly Lawford-Smith, Gender-Critical Feminism (Oxford University Press, 2022), 16.

[3] These are all descriptors that gender-critical commentator Abigail Schrier uses in the first few pages of her book, Irreversible Damage: The Transgender Craze Seducing Our Daughters (Washington: Regnery Publishing, 2020), 1-2.

[4] Lawford-Smith, Gender-Critical Feminism, 16, cf. Aleardo Zanghellini, “Philosophical Problems with the Gender-Critical Feminist Argument against Trans Inclusion,” SAGE Open 10, no. 2 (2020): https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244020927029, 1,5.

[5] Gender critical feminists, most influentially Kathleen Stock (2018), argue for excluding transgender people from gendered spaces due to a belief that transgender women pose a threat to cisgender (i.e. non-transgender) women. Legal scholar Aleardo Zanghellini (2020) thoroughly debunks this argument, concluding that “the best evidence shows that giving trans women access to women’s spaces does not in fact increase risks to space users’ privacy or safety.” See: Zanghellini, “Philosophical Problems,” 6.

[6] For example, Zanghellini dismantles many of the primary arguments made by gender critical feminists (particularly Stock) for trans-exclusionary practices (Ibid.) The journalist Shon Faye takes a broader approach, contextualizing and critiquing gender-critical feminism and trans-exclusionary policies in her bracing The Transgender Issue: An Argument for Justice (Bristol: Allen Lane, 2021).

[7] Judith Butler, “Why Is the Idea of ‘Gender’ Provoking Backlash the World Over?,” The Guardian, October 23, 2021, https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/commentisfree/2021/oct/23/judith-butler-gender-ideology-backlash.

[8] Gareth Lloyd Evans, Men and Masculinities in the Sagas of Icelanders (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2019), 31; Annette Lassen, “Perseverance and Purity in Flóamanna Saga,” The Journal of English and Germanic Philology 118, no. 3 (January 2019): pp. 313-328, https://doi.org/10.5406/jenglgermphil.118.3.0313, 318.

[9] Vilhjálmur Finsen, ed., Grágás: Efter Det Arnamagnæanske Haandskrift Nr. 334 fol., Stadarhólsbók (København: Gyldendal, 1879): 392; Evans, Men and Masculinities, 18-19; Preben Meulengracht Sørensen, The Unmanly Man: Concepts of Sexual Defamation in Early Northern Society, trans. Joan Turville-Petre (Odense: Odense University Press, 1983), 18-20; Ármann Jakobsson, “The Trollish Acts of Þorgrímr the Witch,” Saga-Book 32 (2008): 63.

[10] hverngi carla sið (any manly habits).

[11] Vilhjálmur Finsen, ed., Grágás: Islændernes Lovbog i Fristatens Tid, Udgivet Efter Det Kongelige Biblioteks Haandskrift, vol. 2 (København: Brødrene Berlings Bogtrykkeri, 1850), 47.

[12] Evans, Men and Masculinities, 47.

[13] The men claim that hann ekki í æði sem aðrir karlar, heldr var hann kona ina níundu hverju nótt ok þurfti þá karlmanns (he was not in nature as other men, rather he was a woman every ninth night and then ‘needed’ a man). Jóhannes Halldórsson, ed. Kjalnesinga Saga, Vol. XIV. Íslenzk fornrit (Reykjavík: Hið Íslenzka Fornritfélag, 1991), 134.

[14] Evans, Men and Masculinities, 47-49.

[15] Þorgils þessi hefir verit í vesöld ok ánauð, ok óvíst er mér, hvárt hann er heldr karlmaðr en kona (This Þorgils has been in misery and suffering and it is not known to me whether he is either a man or a woman). Þórhallur Vilmundarson and Bjarni Vilhjálmsson, eds. Harðar Saga. Vol. XIII. Íslenzk Fornrit. (Reykjavík: Hið Íslenzka Fornritfélag, 1991): 305.

[16] Þorgils decides skera á geirvörtuna (to cut into [his] nipples). Ibid., 288-289.

[17] Evans, Men and Masculinities, 61.

[18] Sara Ahmed, “Feministkilljoys,” Feministkilljoys (blog), October 31, 2021, https://feministkilljoys.com/2021/10/31/gender-critical-gender-conservative/.

[19] Jóse Esteban Muñoz, Cruising Utopia: The Then and There of Queer Futurity (New York: New York University Press, 2009), 27.

[20] I have linked to the bipartisan campaign ‘Freedom for All Americans’, which in partnership with The Equality Federation, has collated anti-transgender legislation and policies filed on their website (https://freedomforallamericans.org/legislative-tracker/anti-transgender-legislation). The American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) also tracks the status of this legislation on a weekly basis (https://www.aclu.org/legislation-affecting-lgbtq-rights-across-country).

[21] See: Sonja J. Ellis, Louis Bailey, and Jay McNeil, “Trans People’s Experiences of Mental Health and Gender Identity Services: A UK Study,” Journal of Gay &Amp; Lesbian Mental Health 19, no. 1 (February 2015): pp. 4-20, https://doi.org/10.1080/19359705.2014.960990.

Cover Image. Hvalsey Church, a fourteenth ruin in the abandoned Greenlandic Norse settlement of Hvalsey (Qaqortoq, Greenland). Available through Creative Commons.

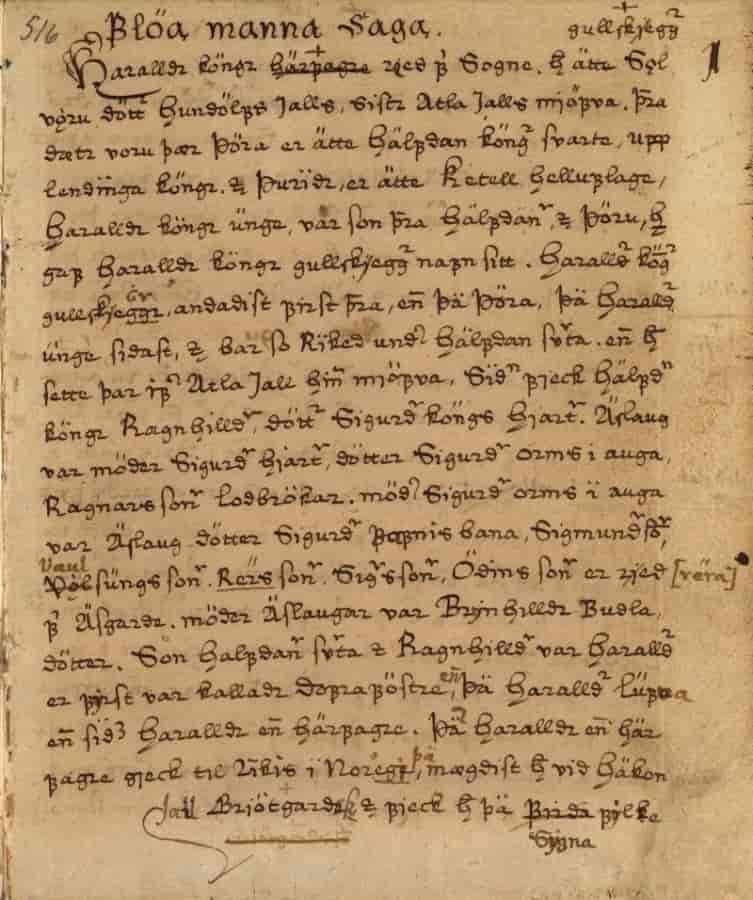

Figure 1. The first page of Flóamanna saga, from the seventeenth-century manuscript AM 516 4to, held in The Árni Magnússon Institute (Stofnun Árna Magnússonar í íslenskum fræðum). Available in the public domain.

Leave a comment