…or, how I learned to stop worrying and love the book…

James Michael Yeoman

This is the second of a two-part discussion, which explores the creation and contents of my book, Print Culture and the Formation of the Anarchist Movement in Spain, 1890-1915, which was published last autumn. In part I, discussed my relationship with my own work, and my thoughts on its value and relevance. Here, I provide a summary of the main interventions made by my book.

II.

Anarchism, as a political movement, originated in the mid-nineteenth century, as something of a combination of the anti-authoritarian, anti-centralisation impulses of radical republicanism, and the mass, revolutionary goals of socialism. Anarchists called for a complete overhaul of society, abolishing capitalism, religion, and the state, without any of the compromises or intermediary phases advocated by democratic socialists and Marxists, such as political parties or a worker’s dictatorship. In later years, the movement would also incorporate anti-racism, anti-imperialism, sexual liberation, and gender equality into its broad remit of revolutionary goals, setting it apart from almost all other contemporary leftist movements in terms of its scope and commitment to end oppression of all forms.

depicting the bombing of the Líceo Theatre in Barcelona

by the anarchist Santiago Salvador Franch.

While anarchist ideas found solid support in the Spanish labour movement from the late 1860s on, by 1890 the movement was in disarray, fractured by doctrinal splits between those who saw unions as the vehicle for revolution, and those who saw them as a platform for reformist shills. As the anarchists lost touch with the wider working class, some turned to terrorism in an attempt to provoke revolution, prompting a brutal response from the Spanish state.[1] Hundreds of women and men were imprisoned, tortured, exiled, and executed simply for holding anarchist ideas, most of whom had nothing to do with the anarchist bomb-throwers and assassins of public imagination [figure 8].

Despite this, the movement in Spain not only survived this period, but also by the end of the First World War had grown into the largest expression of anarchist ideas in world history, with its syndicalist federation (Confederación Nacional del Trabajo: CNT) claiming 800,000 members and on the verge of launching some of the most significant strikes and insurrections ever seen in Spain.

My research focuses on the years between these points: a time of experimentation, success, failure, pessimism, and hope for anarchists in Spain. From 1890 to 1915 the movement had no stable organisation, no recognised leader or unchallenged theorist, no single trajectory or grand strategy for revolution. Rather, befitting a movement that abhorred centralised power, anarchism in Spain reformed itself around a loose network of affinity groups across the country: local activists seeking to advance their ideas in the workplace, educators holding night schools in taverns for women, men and children, and—crucially—comrades coming together to publish books, pamphlets and periodicals, through which anarchist ideas were expressed and shared across villages, cities, regions, countries and continents.

Publishing underwrote every aspect of anarchist practice at this time. Almost 300 titles were launched by anarchist groups in Spain from 1890-1915, who published around 7,300 issues between them. Every sizeable population produced a paper in this period, from Cádiz on the southern coast to Irún on the Basque-French border, and La Coruña on the Atlantic north to Valencia on the Mediterranean [map 1]. Anarchist print was distributed to every corner of Spain, where correspondents would hand out papers or read to their illiterate comrades, and relate the affairs of their locality in letters back to the publishers, many of which would then be published in future issues [map 2].

Map 1. Areas of Anarchist Publishing in Spain, 1890-1915.

Map 2. Distribution of La Protesta (La Línea de la Concepcion), 1901-1902.

This two-way exchange between readers and producers gave the pages of the anarchist press a kaleidoscopic quality, filled with philosophy, poetry, union news, fundraisers for prisoners, and notices from estranged families of migrant workers across the Atlantic. The stock cover of my book is an inadvertently apt representation of how I visualise this print culture, with publishing groups forming nodes that linked the movement together through multi-directional exchanges.[2]

With all of this in mind, I push back on suggestions that the study of print, or culture more broadly, within political groups is irrelevant to ‘what actually happened’ or ‘what a movement does in practice’.[3] On a practical level, print is often the only source of information for the researcher on what actually happened. To dismiss it, or to treat it as solely a repository for information, ignoring its creation and function, is misguided, and overlooks the fact that one of the key things that anarchists in Spain did in practice was produce, distribute, and read printed materials, seeing this as valuable political work. Engaging in print culture was not the only thing that anarchists in Spain did, but it was perhaps the most universal practice within the movement and one which complimented all other activities: ‘We the anarchists’—wrote the anarchist theorist, Ricardo Mella, in 1902—’work for the coming revolution with words, with writings and with deeds…the press, the book, the private and public meeting are today, as ever, abundant terrain for all initiatives’.[4]

Figure. 8. Soledad Gustavo (3 December 1929)

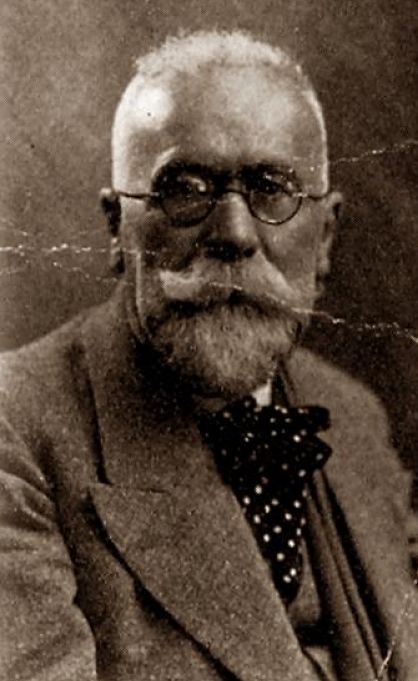

Figure 9. Federico Urales (c.1942).

A loose, informal structure had its strengths and weaknesses. Publishing groups gave anarchism in Spain a semblance of coherence which was lacking in its porous ideology, making it possible to speak of a movement rather than a collection of disparate groups and individuals. Yet fragilities ran throughout this structure, not least because papers often buckled under financial pressures and state repression. At the same time, a reliance on print culture caused frictions in the wider movement. Access to money, literacy, and the means of producing media gave publishers authority and influence, making them ‘informal elites’. Publishers could hold sway over large sections of the movement, with little sense of democratic process or accountability. This provoked disputes within and between publishing groups, subsequent splits, and the creation of rival papers. Even the most prominent individuals in anarchist publishing could be embroiled in arguments and lose their standing, as happened to the pioneering anarchist-feminist Soledad Gustavo and her husband Federico Urales, who together edited the key publications of the movement until they were ostracised in 1904 [figures 8 and 9].[5]

It would be wrong, therefore, to suggest that a flourishing, dynamic media culture was the goal for revolutionaries who aimed for the immediate destruction of all forms of oppression. Anarchists in Spain were aware that something more was needed for this objective, though their ideas of what this would be differed. A small minority advocated forming a vanguard of revolutionary cells, committed to pushing the revolution forward through direct, violent action. From 1900 onwards, a growing part of the movement placed their hopes on ‘modern’, ‘rational’ education, which would lift the veil of ignorance which hung over the working class and help them to realise their own emancipation. A little later, many within the movement turned back towards the idea of organising the working class through unions, placing their hopes in the idea of a mass syndicalist confederation and the revolutionary power of the general strike.

The CNT which resulted from these efforts did not emerge out of nowhere, but rather explicitly built upon the cultural networks that had sustained the movement over the previous two decades. The founders of the CNT knew the value of print to organising the anarchist movement in Spain and made the publication of a central, national paper their priority. This was achieved with the transformation of the CNT organ Solidaridad Obrera into a daily publication in 1916, which soon dwarfed the output of every other paper in Spain.[6] Anarchist groups now refrained from launching new publications and closed their existing titles, which they viewed as redundant.

during the early twentieth century.

Although it never lost its heterogeneity, its regional differences or its prolific, ephemeral, and diverse print culture, anarchism in Spain was entering a new era as a more organised and coherent mass movement, supported by a single paper with a large readership. In assisting this development, anarchist publishers across Spain oversaw a contraction in the political culture they had created, viewing this as a price worth paying in the pursuit of the revolution.

Scholarship—particularly Anglophone scholarship[7]—on the anarchist movement in Spain has primarily focused on the era of the CNT: on the workings of this organisation, on the strikes and insurrections instigated in its name, on its leading figures and detractors and, above all, on the social revolution launched by the movement in the early stages of the Spanish Civil War of 1936-39. Compared to this post-1915 period, the earlier anarchist movement in Spain has been regarded as confused and confusing, illusory and, by some, unremarkable. With few other sources from this period, with very few memoirs of turn-of-the-century activists, and the impossibility of conducting oral histories with long-dead activists and a complete absence of organisational records, print is the only means to evaluate the movement in its own words, the only meaningful indicator of anarchist identity and practice.[8] For a researcher, exploring this print culture can seem a bewildering collection of thoughts, experiences, emotions, traditions and practices; just as it would to a contemporary reader of the anarchist press.

The task of my book has been to reflect the plurality of this movement and the publishers who helped it coalesce and operate, revealing its convergences and contradictions, its successes, mis-steps and contingencies. Anyone looking for clear lessons on how to form a broad, radical, decentralised movement in this historical example may be disappointed, but the wider account may also give them grounds for optimism. Using very limited means and in the face of extreme hostility, the anarchist movement in Spain not only survived but went on to provoke profound social change, in large part thanks to the efforts of those who created and exchanged books, pamphlets and periodicals over the turn of the twentieth century. What they did was talk to one another across social and geographic boundaries, what actually happened was that they changed the world.

James Michael Yeoman is an independent researcher who completed his PhD at the University of Sheffield in 2016. His publications include Print Culture and The Formation of the Anarchist Movement in Spain, 1890-1915 (Routledge, 2020), ‘The Spanish Civil War,’ in C. Levy and M. Adams (eds), The Palgrave Handbook of Anarchism (Palgrave MacMillan 2018) and ‘Salud y Anarquía desde Dowlais: The translocal experience of Spanish anarchists in South Wales, 1900-1915’, in International Journal of Iberian Studies 29:3 (2016). James co-hosts the radical history podcast ‘ABC with Danny and Jim’ with Danny Evans (Liverpool Hope University), which you can find here: https://anchor.fm/abcwithdannyandjim. Follow James on Twitter, contact him at jamesmyeoman@gmail.com, or find out more about his research.

[1] For an excellent overviews of anarchist ‘propaganda by the deed’ see Constance Bantman, ‘The era of propaganda by the deed,’ in Carl Levy and Matthew Adams, The Palgrave Handbook of Anarchism (Palgrave Macmillan, 2018), 371-387.

[2] A brilliant interactive map of anarchist publications in the USA created by Kenyon Zimmerman is available here: https://depts.washington.edu/moves/anarchist_map-newspapers.shtml

[3] Marcel van der Linden, ‘Second Thoughts on Revolutionary Syndicalism,’ Labour History Review 63.2 (1998), 183.

[4] La Protesta (La Linea de la Concepcion), 7 June, 1902, 1.

[5] For Spanish readers, a large collection of Gustavo and Urales’s seminal journal, La Revista Blanca, is available here: http://hemerotecadigital.bne.es/results.vm?q=parent:0002860475&lang=es

[6] A huge collection of Solidaridad Obrera as well as several other papers of the movement are available here: http://cedall.org/Documentacio/Castella/cedall203500000.htm

[7] An excellent bibliography on English-language studies of anarchism in Spain is provided by Chris Ealham in the introduction to José Peirats, The CNT in the Spanish Revolution, vol.3 (ChristieBooks, 2006), available here. To this I would add my friend Danny Evans’s Revolution and the State: Anarchism in the Spanish Civil War: 1936-1939 (AK Press, 2020) as essential reading.

[8] Later periods in the history of anarchism in Spain are well-served by these alternative sources. Hundreds of autobiographies were published by anarchists from the 1930s onwards, and from 1975 a huge amount of oral histories were collected with activists, including many women who feature far less in other sources. Official documents of the CNT are also available from the 1930s.

Figure 7. Collection of anarchist newspapers published in Spain during the early twentieth century. Available in the public domain and here.

Figure 8. Front cover of Le Petit Journal (Paris), 25/11/1893, depicting the bombing of the Líceo Theatre in Barcelona by the anarchist Santiago Salvador Franch. Available in the public domain and here.

Figure 9. Teresa Mañé y Miravet (pseud. Soledad Gustavo) (3 December 1929), unknown artist, signed by German anarchist and historian Max Nettlau. Available in the public domain and here.

Figure 10. Joan Montseny i Carret (pseud. Federico Urales) (c.1942), unknown artist. Available in the public domain and here.

Map 1. Areas of Anarchist Publishing in Spain, 1890-1915. Attribution: James Michael Yeoman and James Pearson.

Map 2. Distribution of La Protesta (La Línea de la Concepcion), 1901-1902. Attribution: James Michael Yeoman and James Pearson.

Leave a comment