C. Annemieke Romein

Let us assume you are governing an early modern ’country’: how should you provide order? How do you keep its inhabitants safe? And how might you organise governance and policy-making? Most researchers who deal with these questions tend to focus on principalities or kingdoms. With this blog post I would like to point out the importance of precision when we talk about power, by addressing two basic concepts that are often misused in research on early modern governance and political-institutional research: ‘absolutism’ and ‘the state’. Finally, I want to focus on precisely how governance on the European mainland was organised (approx. the 16th to 18th century) through ordinances in both principalities and (federation-) republics, to demonstrate the imbalance in historical knowledge resulting from this conceptual misuse.

No absolutism?

Although you – as a prince ruling a principality – will have several advisors at hand (to whom you might or might not listen), you are likely to take a lot of decisions on matters of order and security yourself. But, do not think of your decisive power as ‘absolutism’! That term was invented after the French Revolution, like the most –isms.)[1] Despite that power, there are laws you are subjected to: divine law and the law of nature. Moreover, traditons need to be minded too.

Of course, an early modern prince could become a so-called Absolutus Dominatus.[2] However, that meant that tyrannical rule was looming, which was an illegal form of government and power abuse which would threaten the population as well as the fatherland. The term tyrant should not be confused with the term despot. Mario Turchetti distinguishes between the two:

‘Despotism is a form of government which, while being authoritarian and arbitrary, is legitimate if not legal, in some countries, whereas tyranny, in the most rigorous sense, is a form of government which is authoritarian and arbitrary and which is illegitimate and illegal, because exercised not only without, but against the will of the citizens, and also scorns fundamental human rights.’[3]

The arbitrary rule (not ‘absolutism’) that would result from tyranny meant that a prince could rule without respecting the law – except for the laws of nature and the God-given laws.

Absence of the s-word?

You may notice that I am talking about princes and their principalities (e.g. kingdoms). However, before I can turn to that other governmental system, I need to address the elephant in the room: The “s-word” I am avoiding: State. My dissertational research explained why there was no such thing as a state in the seventeenth century. The era of dynastic warfare within Western Europe, it has often been assumed that the seventeenth-century coincided with and even accelerated the development of the planned bureaucratic state. Sociologist, political scientist, and historian Charles Tilly became famous for posing his thesis: ‘War made the state, and the state made war,’ which suggested that warfare demanded a new development within the state-building process to cope with significant fiscal demands.[4] This development did meet with opposition, but, according to Tilly, the objections came from outsiders to these activities.

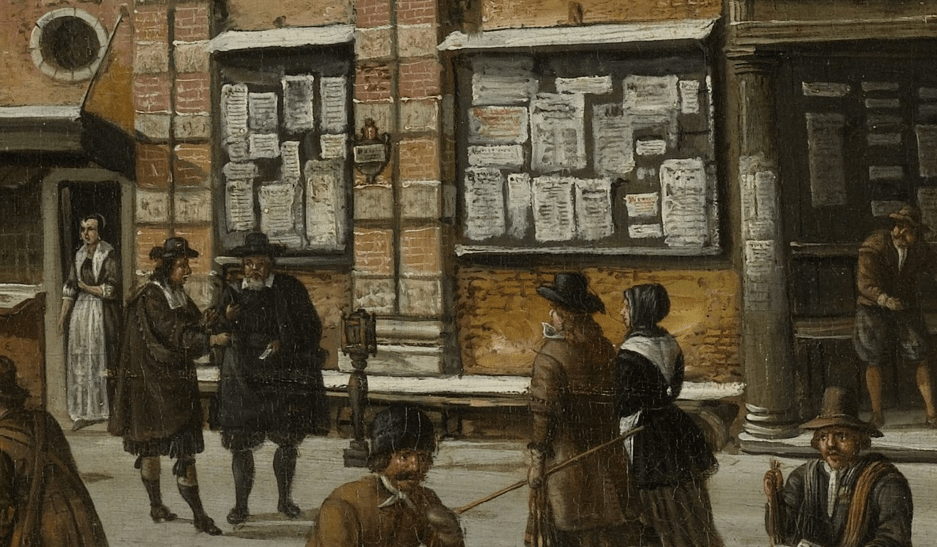

Abrahamsz. Beerstraten, 1640 – 1666. Oil Painting, 84cm × 100cm.

However I argue that there was no deliberate – or accidental – state-building going on at the time. The first argument against state-building lies in the use of the term state. Applying that modern-day term in the early modern context flaws our understanding of a state as it is loaded with connotations and presumptions. Both constitutional and legal historians suggest that the term state in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries did not have the modern meaning of a public institution. Hence, applying the term gives rise to needless confusion.

In our current usage, the concept of state refers to both a government as a legal person, controlling a country, and to the country itself.[5] The term state in the seventeenth-century vocabulary should be understood as what we would now see as the state of the union, or the state of an argument, not even close to the current meaning of a nation-state. In other words, state referred to a condition of something or someone.[6] Applying a modern-day term is anachronistic and superfluous. We can simply call the political entities for what they were: kingdoms, principalities, duchies, counties, imperial cities, or federations. A precise word-choice allows us to keep a sharp focus, without – unconscious – contemporary connotations that have crept into the historical understanding we have of a state.

The second argument against state-building in this period, is that in the historical reality of the seventeenth century, there were no states.[7] Though there were also imperial cities and (federation-) republics, what existed were dominions: lands in the hands of dynasties, without clearly marked borders, but which were not legal entities. Within feudal structures, these lands had become hereditary, intimately tying the princes and their nobility together. The absence of states, or rather, the presence of dynastically ruled lands is of crucial importance to understanding early modern societies.

Influential sociological interpretations of history – such as Tilly’s and Max Weber’s – have shifted the focus to the institutions (organisation of power), ignoring the legitimacy of power (nature of power).[8] By ignoring the nature of power, it becomes difficult, if not impossible, to explain their critique on warfare, bureaucracy, and taxations. Search for glory, religious conversions, or wars of succession: all could personally trigger disputes amongst families. In short, Tilly’s thesis does not apply to the early modern period, due to the absence of states; dynasties waged war to protect and expand their dominion(s).

Governance and ordinances

Let us return to the question: in the absence of statehood, how does an early-modern prince implement governance on order and security? That – automatically – brings us to regulations and how these were implemented. In the 1990’s a significant project regarding police-ordinances started at the Max-Planck-Institute for Legal History in Frankfurt am Main, led by prof. Karl Härter and prof. Michael Stolleis. It has resulted in a repertory of ordinances on 68 areas (principalities and imperial cities), ranging from Sweden, Denmark to Switzerland and Austria. However, most of them are part of the Holy Roman Empire.[9]

What are police-ordinances? ‘Police’ is the English translation of Policey; which has a much broader meaning in the police-ordinances of the early modern era. Policey concerned the whole of – that is, both communication of and debate on – normative rules. Its creation, implementation, enforcement and the maintaining of ordinances all aimed at coercing society towards the common good, and subsequently allowing it to achieve welfare. These measures were responses to immediate threats, but they were not just reactive. They also aimed at a lasting result by communicating the government’s view on how such situations could be avoided in the future.[10] They also contained information as to whom had to correct those who did not obey and what the penalty would be. After their announcement, the new rules were affixed to known places (e.g. church doors, market places, city hall). Such an announcement made them official, for if a rule remained unknown to the public, it could (and would) not be obeyed.

Thus, a prince would discuss a perceived problem with his advisors, and then they would draw up a rule to prevent an undesired situation from (further) happening again. Requests from subjects could also lead to a juridification of norms. Hence, we talk about normative rules rather than laws or legislation, as they were not necessarily top-down implemented.

The above map shows – in light green – the areas that were studied within the MPIeR ordinances-project; dark-green are other initiatives. Do notice that most of the research focuses on small/rural principalities or imperial cities.[11] The latter ruled only a small dominion. Hence, the exerted power was done by a relatively small group of people, and there was little hierarchy.

Now for that other governmental system, the republic: how did the Dutch Republic, or the Swiss Confederation organise their policy?[12] Or indeed, Venice and other Italian City-States that did have an extensive dominion? The Habsburg Netherlands – current-day Belgium – has a long tradition of republishing rules. Since 1846 the Royal Commission for the Publication of Ancient Laws and Ordinances has published volumes which would be interesting to involve in an international comparison. Even though the Habsburg Netherlands were part of the dynastic agglomerate with the Habsburg-Spanish king, this ruler was far away which gave a different dynamic then were he in Brussels. The Dutch Republic and Switzerland each decided to go their own way, which could possibly have led to their own approach of problems.

However, an initial comparison between Flanders and Holland suggest that the differences may not have been as massive as has assumed.[13] The nature of republics is a neglected topic of research. We are aware of huge differences between e.g. the Kingdom of France and the Kingdom of Sicily. Nevertheless, we can hardly tell the difference between how the Grisons[14] and Holland differed from one another. The question ‘what is a republic’ leads to the awkward, superflous reaction that both federation-republics lacked a prince.

***

To conclude: we know a lot about principalities and small city-state governments and how they organised their policy. However, we have very little systematic knowledge of federation-states/ republics. Several projects in the Low Countries have started the past few years, such as REPUBLIC and A Game of Thrones?. Much more could and should be done, especially regarding the interconnectedness of governments, norms and ideas.

Christel Annemieke Romein is an NWO-VENI Postdoctoral Researcher at Huygens ING, Amsterdam. Here she works on the early modern political-institutional/ legal history of federation-republics during the period 1576-1702. In particular, she focusses on Holland, Gelderland and Berne (CH) in a comparative perspective. In her research, she fuses the fields mentioned above with Digital History.

[1] Glenn Burgess, Absolute Monarchy and the Stuart Constitution (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1996), 17–62; Richard Bonney, ‘Absolutism: What’s in a Name?’, French History, 1, no. 1, (1987): 93–117.

[2] The legal phrase absolutus Dominatus should not be confused with the French monarchie absolue. This French phrase merely indicated the French king’s independence from other earthly authorities (for example the Pope). See for instance: J.B. Collins, The State in Early Modern France, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009).

[3] Mario Turchetti, ‘“Despotism” and “Tyranny” Unmasking a Tenacious Confusion’, European Journal of Political Theory 7, no. 2, (1 April 2008): 160, https://doi.org/10.1177/1474885107086446.

[4] Charles Tilly, ‘Reflections on the History of European State-Making’, in The Formation of National States in Western Europe, ed. Charles Tilly, vol. 38, (Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1975), 42.

[5] Robert C. F. von Friedeburg, ‘How “New” Is the “New Monarchy”? Clashes between Princes and Nobility in Europe’s Iron Century’.’, Leidschrift, 27, (2012), 22.

[6] Robert C. F. von Friedeburg, Self-Defence and Religious Strife in Early Modern Europe: England and Germany, 1530–1680, St. Andrews Studies in Reformation History, (Burlington Vt.: Ashgate, 2002), 16.

[7] Robert C. F. von Friedeburg, ‘State Forms and State Systems in Modern Europe’, European History Online (EGO) Published by the Institute of European History (IEG), Mainz (blog), 3 December 2010, http://www.ieg-ego.eu/friedeburgr2010-en.

[8] Robert C. F. von Friedeburg, ‘State Forms and State Systems in Modern Europe’, European History Online (EGO) Published by the Institute of European History (IEG), Mainz (blog), 3 December 2010, http://www.ieg-ego.eu/friedeburgr2010-en.

[9] The repertory will soon be online, after a significant update of the database-system by dr. Andreas Wagner.

[10] Karl Härter, ‘Security and “Gute Policey” in Early Modern Europe: Concepts: Laws, and Instruments’, in: The Official Journal of Quantum and Interquantum. Special Issue: Human Security, 35:4, (2010), pp. 41-65, here p. 42.

[11] See for instance, Thomas Simon, ‘Gute Policey’. Ordnungsleitbilder und Zielvorstellungen politischen Handelns in der Frühen Neuzeit, (Frankfurt a/Main: Klostermann 2004).

[12] André Holenstein, Thomas Maissen, Maarten Roy Prak, The Republican Alternative: The Netherlands and Switzerland Compared, (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press 2008) OA: https://oapen.org/search?identifier=340047

[13] See output: https://www.nwo.nl/onderzoek-en-resultaten/onderzoeksprojecten/i/45/28645.html

[14] Randolph C. Head, Early Modern Democracy in the Grisons: Social Order and Political Language in a Swiss Mountain Canton, 1470-1620, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press 2002).

Figure 1. Detail from The Paalhuis and the New Bridge (Amsterdam) during the winter, by Jan Abrahamsz. Beerstraten, 1640 – 1666. Oil Painting, 84cm × 100cm. Understood to be in the public domain. Source: http://hdl.handle.net/10934/RM0001.COLLECT.5966

Figure 2. Provided by the author. Blank map of the Holy Roman Empire in 1648, with data from: https://www.rg.mpg.de/publikationen/repertorium_der_policeyordnungen

Leave a comment