Dr Karie Schultz

In recent years, the value of universities––and especially of a humanities education–– has been hotly contested. Discourse has focused on how the humanities might equip students to think critically about the contemporary problems with which they are faced. Turning our focus toward the history of universities, it is evident that these institutions have always served this purpose. Early modern universities were wealthy, powerful institutions with vast political and cultural significance.[1] My research has focused on how university education informed seventeenth-century students’ ideas about multiple religious and political conflicts in Europe. In this post, I want to suggest how examining the studies and experiences of students helps us to better understand early modern political and religious changes on a transnational scale.

The Cultural Significance of Early Modern Universities

In the seventeenth century, students entered universities at a young age, usually around 13 or 14 years old (which is inconceivable to us today!). They undertook courses in a range of subjects, including but not limited to ethics, logic, rhetoric, and metaphysics.[2] When they graduated, many became ministers, lawyers, university regents, or statesmen. In these positions, they were able to affect policy developments on a broad social basis. This was especially the case in Britain and Ireland (the main geographic focus of my research) where people witnessed unceasing conflicts, such as the civil wars of the 1640s, the Glorious Revolution in 1688, and the Acts of Union in 1707. University-educated individuals responded to these problems by transmitting the ideas that they learned about political life and theology in the universities to the wider population through sermons, books, political pamphlets, and ordinary conversations. Those in positions of political prominence also used the universities to enforce conformity. For example, the Scottish Covenanters purged the universities of those who opposed their agenda throughout the 1640s while ensuring that the curriculum trained students to support their cause.[3] Although those in political power sought to control university education, these institutions offered students multiple opportunities to challenge or strengthen their religious and political allegiances.

Student Migration and Identity Formation

Even though the universities had cultural significance at home, early modern students were also highly mobile. Students undertook part––if not all––of their university education at universities outside their native country. This was possible because Latin was the universal language. Students attended lectures and took notes in Latin, while the lengthy treatises they read on theology, politics, and other pertinent subjects were also in Latin. As a result, universities throughout Europe provided students with an education which transcended geographical borders. However, early modern universities were also confessional. This meant that the education offered adhered to the confessional affiliation of the institution. Universities in England and Scotland, for example, required students to subscribe a Protestant Confession of Faith to attend. This requirement forced Catholic students to travel overseas for their education. Catholic national colleges consequently emerged throughout continental Europe (primarily in France, Italy, Spain, and the Low Countries). At these colleges, Catholic students from England, Scotland, Wales, and Ireland could train to become priests or missionaries, or they could enter alternative careers upon graduating.[1]

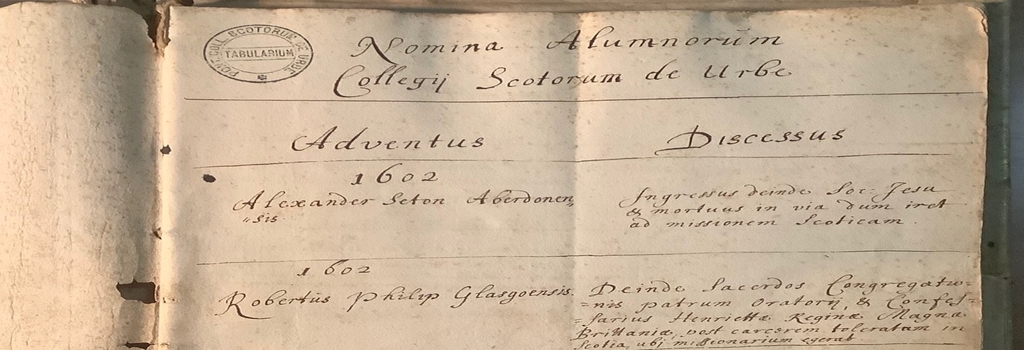

During my recent nine-month postdoctoral fellowship at the British School at Rome, I studied the Pontifical Scots College and the Venerable English College in Rome to understand the studies and experiences of students at both institutions. English and Scottish students who studied in Rome often faced tensions between their national and confessional identities. On the one hand, students sought to preserve their national distinctiveness in the eyes of the Catholic Church hierarchy, especially following the dynastic Union of Crowns in 1603 and subsequent attempts to consolidate the English and Scots Colleges into one institution. On the other hand, they also trained alongside students of multiple nationalities to spread Catholicism globally through mission work. The need to contribute to a confessional goal which transcended geographical borders whilst maintaining their national distinctiveness resulted in many institutional conflicts with, and challenges to, the Catholic Church hierarchy throughout the seventeenth century.

Rector to ease national tensions.

However, transnational mobility was not unique to Catholic students. Reformed students from the British Isles also attended universities in the Low Countries and the German-speaking lands, such as the University of Heidelberg and the University of Leiden. Students who migrated to Reformed universities also established confessional communities through local churches which, like those of Catholic students, transcended national borders. The experiences of students in the early modern period therefore raise multiple questions about the relationship between international mobility, education, and identity formation that are worth further exploration.

Since the beginning of September 2021, I have been pursuing such research questions further during my Leverhulme Early Career Fellowship at the University of St Andrews. For the next three years, I will study the transnational and cross-confessional mobility of seventeenth-century students from Britain and Ireland to continental Europe. One of my aims is to challenge the emphasis on the printed text as the primary evidence of intellectual culture. Using lecture notes, philosophical theses, dictates, and correspondence scattered throughout archives in Europe, I hope to show how political and religious ideas were transmitted on a broader social basis outside of printed treatises. Furthermore, by examining the studies and experiences of Catholic and Reformed students together, it is possible to interrogate fundamental assumptions about the rigidity of confessional and national identities through the lens of university education. Students are therefore a crucial but often overlooked category of migrants who offer us new perspectives on how education informed international political and religious developments during the early modern period.

Dr Karie Schultz is a postdoctoral researcher in the Department of History at the University of St Andrews, UK. Prior to this she held a postdoctoral fellowship at the British School at Rome. Her PhD thesis entitled “Political Thought and Protestant Intellectual Culture in the Scottish Revolution, 1637-51” was completed at Queen’s University Belfast (2020).

All figures are the author’s own and require permission to be re-used.

[1] Liam Chambers and Thomas O’Connor, eds., College communities abroad: Education, migration and Catholicism in early modern Europe (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2017); Tom McInally, The Sixth Scottish University: The Scots Colleges Abroad: 1575 to 1799 (Leiden: Brill, 2012).

[1] Mordechai Feingold, ed., History of Universities, 33 vols. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1975-2020); Hilde de Ridder-Symoens, ed., A History of the University in Europe, Volume II: Universities in Early Modern Europe (1500-1800) (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996).

[2] Christine Shepherd, “Philosophy and Science in the Arts Curriculum of the Scottish Universities in the 17th Century,” PhD diss. (University of Edinburgh, 1974).

[3] Salvatore Cipriano, “The Engagement, the Universities and the Fracturing of the Covenanter Movement, 1647-51,” in The National Covenant in Scotland, 1638-1689, ed. Chris Langley (Woodbridge: Boydell, 2020), 146-60; Salvatore Cipriano, “Seminaries of Identity: The Universities of Scotland and Ireland in the Age of British Revolution,” PhD diss. (Fordham University, 2018); Steven J. Reid, ‘“Ane Uniformitie in Doctrine and good Order’: The Scottish Universities in the Age of the Covenant, 1638–1649,”’ History of Universities 29(2):13-41.

Leave a comment