By Julie Holder

When I tell people that I research the nineteenth-century history of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, a very specific idea of an ‘antiquary’ comes to mind: white, male, and middle or upper class. And to a great extent this view is correct. However, that does not mean that women were not engaged in antiquarian activities or wholly excluded from the Society and its museum in Edinburgh.

It was not until 1901 that women could be elected as full members (known as Fellows) of the Society on the same standing as men. However, women contributed to the Society’s development as donors, museum visitors, attendees of the Rhind lectures in archaeology, and Lady Associates.

Lady Associates

A.E. Chalon, R.A., painted in 1839, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

During the nineteenth century, archaeology was a popular pastime for many women, with some becoming prominent pioneers in the field.[1] They were also increasingly involved in historical and art historical studies.[2] In 1868, the admission of women to the Society was discussed in light of the ‘circumstance that several Archaeological Societies in England admitted Ladies as Members’.[3] This led to the establishment of the Society’s first official membership category for women called Lady Associate. The first two women elected were Lady Alicia Anne Scott (1810-1900) in 1870 and Christian Maclagan (1811-1901) in 1871.

Lady Scott was a writer and collector of Scots songs, collector of Jacobite relics, and had directed archaeological excavations on her estates.[4] Maclagan is credited with being Scotland’s first female archaeologist and was an accomplished artist who developed a new technique for taking rubbings of sculptured stones.[5] Maclagan disputed her membership status, requesting that she should either be elected a full Fellow or have her name removed from the Lady Associate list. Unfortunately, Maclagan died the same year that women were finally permitted to be elected as Fellows of the Society.

Other prominent Lady Associates elected between 1870 and 1901 were the Irish antiquarian and artist Margaret McNair Stokes (1832-1900), Egyptologist Margaret Alice Murray (1863-1963), and English historian and archaeologist Ella Sophia Armitage (1841-1931).

Lady Associates were honorary members, limited to 25 at any time, who did not pay membership fees. Although they could submit communications to be read at meetings by male Fellows, they were not permitted to present them in person. This situation limited women’s opportunities to contribute to in-person discussions of historical objects or shape the development of the museum’s collection. However, the establishment of this new membership group reflected the Society’s recognition of the scholarly work being produced by women involved in antiquarian and archaeological studies at this time, eventually leading to full membership rights for women in 1901.

Stirlingshire by Christian Maclagan, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

Women as collectors and donors

Although women were not allowed to attend Society meetings, like other members of the public they could visit the museum, attend the Rhind lectures, and donate objects to the collection. My research looked at how the Scottish historical collection expanded from 1832 to 1891 and women were regular contributors.[6]

Between 1832 and 1891, the number of women donating objects to the Scottish historical collection was generally minimal and fluctuated, from only one woman, Miss Walker, from 1832 to 1841, up to 14 different women from 1862 to 1871. The quantity of objects donated each decade by women also fluctuated, with the lowest being five objects from Miss Walker between 1832 and 1841, and the highest being 187 objects donated between 1882 and 1891. Generally donations by men far outnumbered those by women, often coming from Fellows of the Society. Notably, none of the women donors were Lady Associates.

What I found most interesting was that women were not solely donating what could be called ‘feminine’ items, although these were amply represented. Instead, they donated a broad range of objects reflecting different types of evidence from the Scottish past. Some of these items had clear links to historical events or connections to prominent people, including a ring that was a gift from Prince Charles Edward Stuart, pike-heads used during the disturbances caused by the Society of Friends of the People in 1793, and a spur found on the battlefield of Bannockburn.

Other objects reflected evidence of how Scottish people had lived and worked in the past, which were part of collecting the social and cultural history of Scotland, including household utensils, tools and implements, and ecclesiastical items. Women donated exactly the same spread of historical items as men, as can be seen in the 1892 edition of the Catalogue of the National Museum of Antiquities of Scotland in which their names were recorded. In comparison, men donated more ‘feminine’ items than women, including samplers, jewellery, and ladies’ shoes. This suggests that although women were excluded from the Society’s meetings, where the meanings of these objects were discussed, they had similar antiquarian interests to men, and this reflected the broader nineteenth-century middle-class enthusiasm for history and archaeology.[7]

The Sim Collection

Before the Married Women’s Property (Scotland) Act of 1881, married women did not have the legal rights to dispose of their movables in the same manner as single or widowed women. This legal situation materially affected who (and when) women were able to donate objects to the museum. This can be seen in the case of the Sim Collection donated by Mary White of Netherurd House in 1882.

The Sim Collection was the largest donation of Scottish historical objects offered to the museum by a woman between 1832 and 1891 at a total of 156 items, with an accompanying substantial prehistoric collection. The collection had belonged to Mary’s brother, Adam Sim (1805-68), and was inherited by Mary in 1868. But as a married woman her husband had absolute power over her property by virtue of his jus mariti.[8] Mary did not donate the Sim Collection to the museum until 1882 after her husband, Fellow John White, died in 1880.[9] This reflects how Mary could only assume full control of her brother’s property upon widowhood.[10]

We have no indication of Mary’s thoughts on her brother’s collection, which she may have had little interest in and wanted out of her house, or she may have felt it was an important addition to the Scottish national collection. But the fact that it was donated to the museum not long after her husband’s death suggests she had no agency over it while she was married. Mary’s example could explain why I found such limited numbers of donations by other married women during the nineteenth century, who may have wanted to offer items to the museum but were unable to.

This blog post gives a brief snapshot of women’s contributions to the Society’s nineteenth-century history as collectors, donors, and Lady Associates. The most exciting developments in women’s history within the Society no doubt occurred after 1901 and is a subject I look forward to seeing developed by other researchers.

Dr Julie Holder completed her PhD at the University of Glasgow in collaboration with National Museums Scotland in 2021. Her thesis titled ‘Collecting the Nation: Scottish History, Patriotism and Antiquarianism after Scott (1832-91)’ critically examined the relationships between the expansion of the Scottish historical collection in the museum of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland and the development of new ways of understanding Scotland’s material histories. She is currently employed as a part-time tutor at the University of Glasgow.

Twitter: @Julieh80

[1] M. Díaz-Andreu and M. Stig Sørensen, eds, Excavating Women: A History of Women in European Archaeology (London, 1998).

[2] For example, historian and biographer Agnes Strickland (1796-1874).

[3] ‘Anniversary Meeting 30 Nov 1869’, Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland [PSAS], 8 (1870), 229-30.

[4] M. Warrender, ‘Preface’, in Songs and Verses, Lady J. Scott (Edinburgh, 1904), ix-lxiv.

[5] S. Elsdon, Christian Maclagan: Stirling’s formidable lady antiquary (Balgavies, 2004).

[6] J. Holder, ‘Collecting the Nation: Scottish History, Patriotism and Antiquarianism after Scott (1832-91)’ (unpublished PhD thesis, University of Glasgow, 2021). Historical objects were defined as those dated from the twelfth century onwards and I did not include coins or works of art.

[7] See M. Díaz-Andreu, A World History of Nineteenth-Century Archaeology (Oxford, 2007) and B. Trigger, A History of Archaeological Thought, 2nd edition (Cambridge, 2006) for histories of archaeology.

[8] National Records of Scotland, Scotlands People, 1869 Sim, Adam, Wills and testaments, Reference SC36/48/61, Glasgow Sheriff Court Inventories, pp. 455-63 and Reference SC36/51/55, Glasgow Sheriff Court Wills, pp. 275-82. My thanks to Dr Rebecca Mason who advised me and provided comments on the legal information used in this blog post.

[9] ‘Anniversary Meeting 30 Nov 1880’, PSAS, 15 (1881), 3.

[10] In ‘Notices of a Mortar and Lion-figure of Brass’, 52-4 there is reference to a lion-shaped ewer from Adam Sim’s collection being the property of John White.

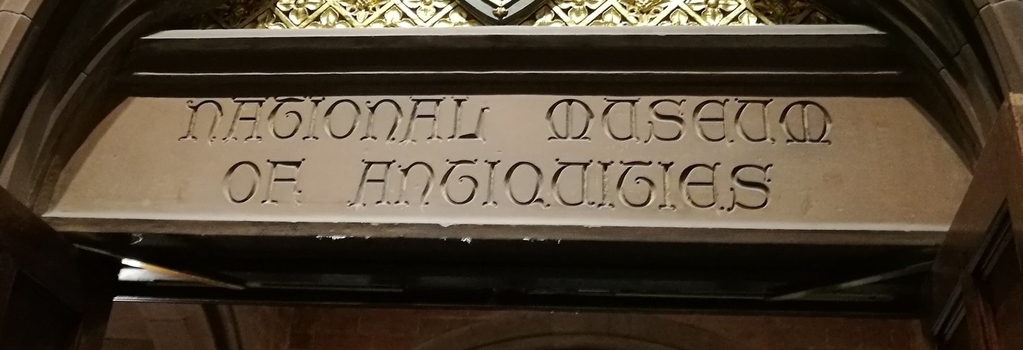

Cover Image. Entrance to National Museum of Antiquities of Scotland, Queen Street, Edinburgh, where the Society’s museum was located from 1891 to 1998. Photo taken by Julie Holder, not to be reproduced without permission.

Figure 1. Lady Alicia Anne Scott, known as Lady John Scott by A.E. Chalon, R.A., painted in 1839. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

Figure 2. Christian Maclagan pen and ink drawing of the Keir Hill, Gargunnock, Stirlingshire by Christian Maclagan. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

Figure 3. Margaret McNair Stokes, by unknown author. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

Leave a comment