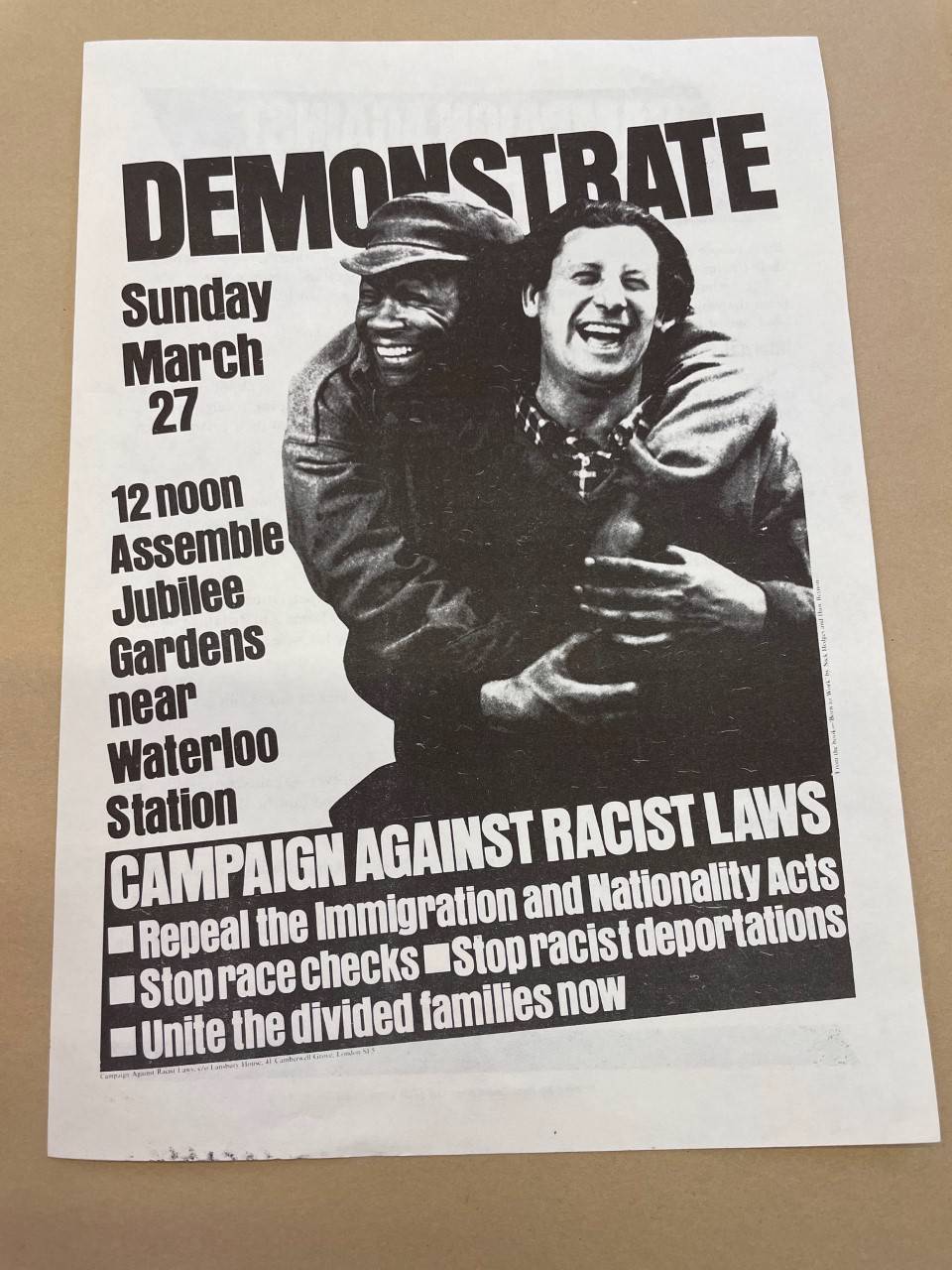

Figure 1: Poster of the Campaign Against Racist Laws

By Amy Grant

Beginning my research into anti-deportation campaigns in Britain during the long 1980s was a depressing experience. I became enveloped by account after account of families and individuals being torn apart by ever-tightening and often arbitrarily administered immigration laws.[1] It became clear that the ‘hostile state’ began its inception long before Theresa May first infamously championed it in 2012, but, our means of resistance, channels of appeal, and overall sense of hope have only declined since the ‘80s.[2] Eventually, however, I began to see the hope within these stories.

To be clear, anti-deportation campaigns should not be romanticized. Taking sanctuary to avoid deportation in a damp church vestry, fighting off immigration officers by force, or spending years fighting bureaucratic court cases whilst your life lies in limbo, is an inherently traumatising experience. Often, such campaigns were not even successful at preventing a deportation, most famously exemplified by the case of Viraj Mendis, who camped out in a Manchester church for 760 days, only for police to eventually break down the doors, unceremoniously drag him out in his pyjamas, and shove him in the back of a police van to Pentonville prison, before deporting him to Sri Lanka. Perhaps surprisingly, a number of anti-deportation campaigns were successful: Victoria Apetor, Nasira Begum, Salema Begum, Amir Kabul Khan, Renoukaben Lakhani, and Pina Manuel, for example, are just a few names of those who won their right to remain in the country after campaigning their case.[3]

What’s more, there is something to be said for the pure perseverance exhibited in these campaigns: the collective diverse community action championed, friendships formed, funding found, and sheer innovative creativeness, that these desperate resisters, activists, vicars, teachers, lawyers, students, and fulltime ‘dole claimers’ alike, were able to achieve in conditions of adversity. I found examples of an elderly Lancashire parishioner storming their local church armed with a sewing needle to collect blood from herself and a Hindu man taking sanctuary in said church, in order to create a dramatic letter of intervention to the Home Office, and a rather macabre publicity stunt.[4] In London, inner-city teachers and parents were hosting mock ‘question time’ press appeals, with their primary school students answering questions in defence of their classmates who were under threat of deportation.[5] And in Birmingham, Asian taxi drivers were rallying via their in car radio system to create an ad hoc diversions to police, whilst a passenger under threat of deportation was spirited away to the sanctuary of a Birmingham mosque.[6]

Although there has been a welcome push to de-centre the historiographic focus on the long 1980s ‘out of the shadows cast by Thatcher’, it equally cannot be denied that the brand of monetarism-cum-individualism which Thatcherism propelled had far reaching ramifications, which fostered a sense of despair and disenfranchisement in many, not dissimilar to that felt by some today.[7] In recent discussions with one life-long voluntary sector activist and academic, he recalled to me that while he would never go as far as to say that Thatcherism was a good thing for society, actually, when there is no funding or governmental incorporation into avenues of the voluntary sector, there is also a freedom.[8] As my research attests, when people collectively hit rock-bottom, they often find surprising strength, in themselves, in their faith, in their neighbourhoods, and chosen communities. Perhaps that is not an entirely depressing precedent to consider in our current climate.

Amy Grant is a PhD candidate historian at the University of East Anglia, under the supervision of Dr Becky Taylor and Dr Camilla Schofield. Their work currently focuses on state, hate, race and church relations in late twentieth century Britain, through the lens of sanctuary campaigns and anti-deportation resistance.

[1] Steve Cohen, Immigration Controls, the Family and the Welfare State, (London, Jessica Kingsley Publishers, 2001).

[2] Dallal Stevens, UK Asylum Law and Policy, (London, Sweet & Maxwell, 2004).

[3] The Ahmed Iqbal Ullah Race Relations Resource Centre in Manchester currently holds the memorabilia from over seventy anti-deportation and immigration campaigns fought in Greater Manchester from 1975-1996.

[4] Author interview with Rev. Paul Weller, campaign leader in the Vinod Chauhan anti-deportation campaign.

[5] https://www.williampatten.hackney.sch.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/Patten-Pages-Issue-175.docx.pdf

[6] Author interview with Shafaq Hussain, campaigner for the Amir Kabul Khan anti-deportation campaign.

[7] Matthew Hilton, Chris Moores & Florence Sutcliffe-Braithwaite, ‘New Times revisited: Britain in the 1980s’, Contemporary British History, 31:2 (2017), pp. 145-165.

[8] Colin Rochester, ‘Plenary Lecture: Voluntary Action in Changing Times: Creating history or repeating It? What have we learned?’, Voluntary Action History Society Conference, Liverpool University, 15 July 2022.

Leave a comment