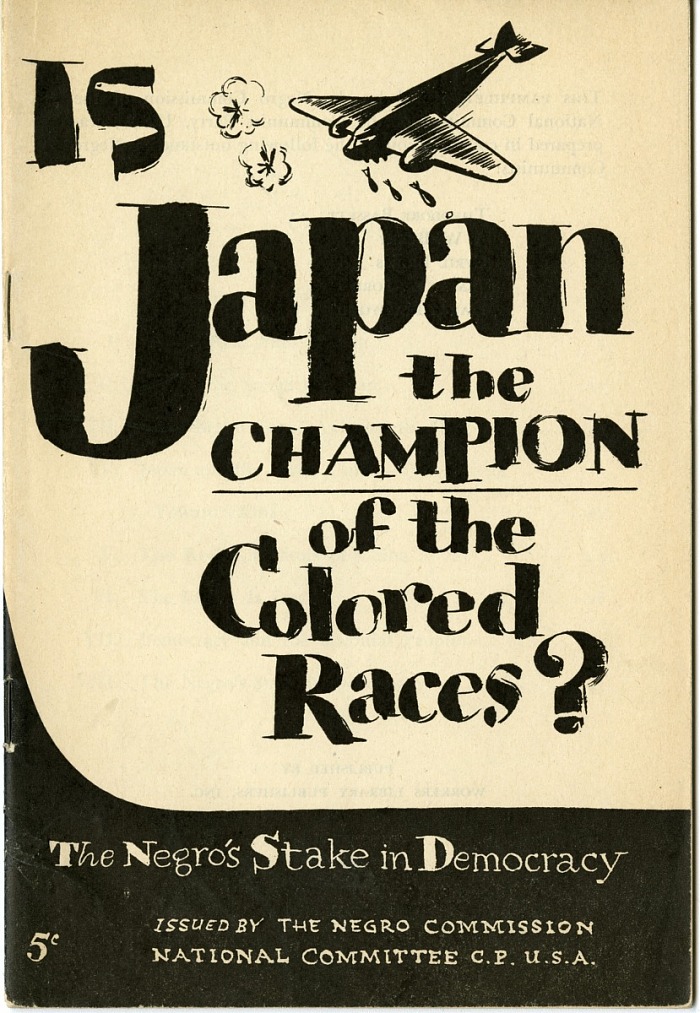

Figure 1: 1938 pamphlet issued by the Negro Commission of the National Committee of the Communist Party, USA

By Dr Sherzod Muminov

For a few early decades of the twentieth century, Japan came to be seen as a champion of the colonized peoples around the world. Behind this image stood Japan’s meteoric rise as the first non-white nation to join the great power club. It had achieved this status through its victory in the Russo-Japanese War—a remarkable feat for a nation that only a half-century prior had been under threat of colonization by European empires. Japan’s victory was met with elation throughout the colonial world; in one example of its resonance, the Turkish author and translator Halide Edib named her son Togo after the admiral Tōgō Heihachirō (“the Nelson of the East”), under whose leadership the Japanese defeated the Russian Baltic Fleet at Tsushima.[1] A few years later, even the Russian communists would view favourably Japan’s triumph over Imperial Russia. In his 1924 poem “Vladimir Ilyich Lenin,” Vladimir Mayakovskii, the “poet of the Revolution,” praised the deathly blows inflicted on the Tsarist forces by the Japanese for exposing the hypocrisy and bankruptcy of the Romanov regime.

The Japanese initiative to have a racial non-discrimination clause added to the Covenant of the League of Nations at the Paris Peace Conference was in part an instance of the nation trying on the garb of the defendant of coloured peoples bestowed on it in the wake of its victory over Russia. In advancing its proposal, Japan—as one of the victorious powers at Versailles that would play a significant role in the League in the subsequent decade—was fully aware of the goodwill of the coloured peoples attached to such a call for racial equality. And while Wilsonianism made the Japanese leaders nervous, the colonisers of Korea and Taiwan saw no contradiction in attempting to write into the Covenant a condition that would guarantee equality to non-white races.

These two episodes won Japan admirers not only among the Asian revolutionaries or independence fighters, but also the advocates for the rights of African Americans. According to one of his biographers, the prominent writer and Pan-Africanist activist W.E.B. Du Bois “virtually anoint[ed] the Empire of the Rising Sun as the lodestar of all the ‘darker races.’”[2] The historian Gerald Horne has written that Japan’s rise as a counterpoint to the white Euro-American empires “did not just have an impact on Washington, it complicated the global correlation of forces as a whole.” Soon “Negro middle class was seemingly flocking to Japan’s banner.”[3] They followed thousands of Asians—and pan-Asianists—who streamed to Japan early in the century in search of education and inspiration for their own nations’ path out of colonial subjugation and racial discrimination.

Many of those Asians, especially Chinese and East Asians who felt first-hand the pressure from the Japanese Empire increasingly willing to throw its weight around, soon saw through the pan-Asianist propaganda peddled by expansionist and right-wing associations in Japan. Their fears that despite its promise of liberating Asia from European colonialism, Japanese imperialism was not much different in its methods and aspirations, found proof in the autumn of 1931, in the so-called Manchurian Incident. Officers in the Japanese Kwantung Army, stationed in northeast China seemingly to protect Japanese residents and business interests, staged an explosion on the South Manchuria Railway, blamed it on the Chinese, and used it all as a pretext to expand Japanese influence to the whole of Chinese Northeast (three provinces of Heilongjiang, Jilin, and Liaoning). Condemned by the League of Nations, Japan left that international organisation and descended into militarist rule that resulted in the war against China (1937), Tripartite alliance with Hitler’s Germany and Mussolini’s Italy, and subsequent defeat in World War II.

Despite the global outcry over the Manchurian Incident, W.E.B. Du Bois, and other civil rights activists such as James Weldon Johnson, continued to defend Japan. Nevertheless, the admiration for Japan was not universal among the African American intellectuals. The title of a 1938 pamphlet issued by the Negro Commission of the National Committee of the Communist Party, USA, inquired: Is Japan the Champion of the Colored Races?[4] One does not have to go deep into this 48-page pamphlet to realise that the answer is an emphatic no. In a devastating critique of Japan’s imperialist policies, the authors of the pamphlet wrote about the “deepest disillusionment…felt by the millions of colored peoples in America, Africa and Asia who once regarded seriously Japan’s claim to leadership of the colored world.” In fact, Japan stood “in open alliance with the worst enemies of the colored peoples”: Mussolini, “the assassin of the Ethiopians,” and Hitler, “who loudly proclaims his contempt for the Negro as an inferior being.” Exposing the hypocrisy of Japanese propaganda claims about building a multi-ethnic paradise in Manchuria, the pamphlet proclaimed that the “Manchurian peasants, like the natives of most of the African colonies, are forces to build roads and railways without pay,” while the “blood of thousands of Koreans, massacred in the struggle for independence…bears witness to the fact that imperialism knows no color.” So much for the Japanese Empire’s promise to liberate the coloured peoples from the imperialism of white colonial powers.

To be sure, the pamphlet betrays the influence of Soviet propaganda of the period, not least in its questionable sources—it quotes the spurious “Tanaka Memorandum” that seemingly outlined a plan for the destruction and conquest of China. Nevertheless, its lucid language clearly tailored to a working-class readership, the broad scope of its analysis, and hard-hitting attacks on the hypocrisies of the Japanese imperial propaganda, make for remarkable reading. Its ideological message aside, such a pamphlet will have provided its readers with an engaging account of Japan’s broken promise to put an end to racial oppression and discrimination.

Dr Sherzod Muminov is an Associate Professor in Japanese History at the University of East Anglia where he researches Japanese and East Asian History, Japanese-Soviet/Russian relations, the Cold War in East Asia, the post-WWII, post-imperial migrations in East Asia, and the international and transnational history of the Soviet system of forced labour camps for prisoners-of-war.

[1] Selçuk Esenbel, “The Impact of the Russo-Japanese War on Ottoman Turkey,” in Japan, Turkey and the World of Islam: The Writings of Selçuk Esenbel (Leiden: Brill, 2011), 148.

[2] David Levering Lewis, W. E. B. Du Bois: The Fight for Equality and the American Century, 1919-1963 (New York: Henry Holt and Co., 2000), 392.

[3] Gerald Horne, Facing the Rising Sun: African Americans, Japan, and the Rise of Afro-Asian Solidarity (New York: NYU Press, 2018), 32, 34.

[4] Negro Commission, National Committee of the C.P. U.S.A., Is Japan the Champion of the Colored Races? (New York: Workers Library Publishers, Inc., 1938).

Leave a comment