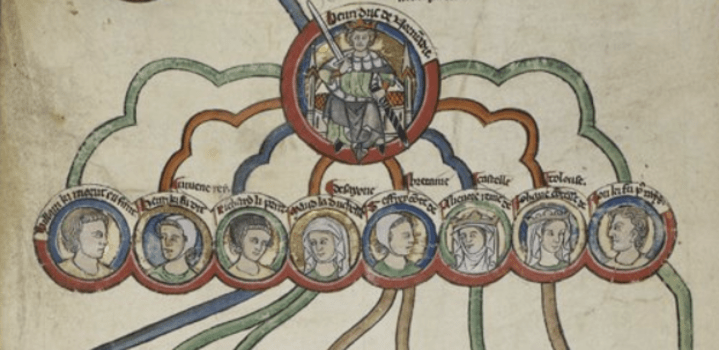

Fig. 1 Henry II and his children, Royal 14 B VI, Membrane 6, British

By Gabby Storey

For most scholars of royal studies, the concepts of corporate or composite monarchies, now fusing with ideas of co-rulership, are important – though not always essential – approaches to apply to the study of monarchy. However, for monarchical studies, looking at the monarchy as a partnership, or a series of partnerships thereof, is a particularly useful foundation for understanding the monarchy as a unit, the power and agency of those surrounding the regnant monarch (usually, but not always a king), and how power and governance functioned across different times and places when taking a longue durée approach.

In particular, co-rulership can be a useful concept to utilise for kings and queens because it tells us more about queens, their power, and administration. Through analysis of royal partnerships, whether that be that of husband and wife, mothers and sons, monarchs and favourites, we gain a better understanding of the involvement of female family members and queens in rulership and governance, their contributions to royal authority and dynastic survival, and the ways in which queens shared power with their co-rulers.

Co-rulership is defined by the sharing of power between two parties: this power share may be uneven, and vary from partnership to partnership i.e. the same amount of power is not shared by each king with their queen, for example, but both parties are active in ruling, whether that be through formal or informal means. Elena Woodacre and Gabrielle Storey have both utilised theories of co-rulership in their works on the queens of England, with Woodacre also arguing for its incorporation in global queenship studies, as well as her hypothesis that all queens were co-rulers.[1] Establishing models of rulership – such as Woodacre and Storey have – can be a useful approach in terms of categorisation and understanding different partnerships across time and place, as many co-ruling partnerships follow similar patterns.

Though the majority of work on co-rulership thus far has been conducted on queens in medieval Western Europe, there are vast opportunities for research across other temporal and geographical areas. In particular, Chinese empresses, Kushite queens, and Byzantine empresses would all benefit from further study both individually and from a co-rulership approach. Utilising a comparative methodology has also proven productive for royal studies work outside of queenship, with a longue durée comparative approach, whether across different regions or not, enabling historians to determine patterns and changes in the exercise of power and authority by rulers.[2]

Fig. 2 One of medieval Europe’s most successful political partnerships, Blanche of Castile and Louis IX. Image: Top, Blanche of Castile and King Louis IX of France; below, author dictating to a scribe, Moralized Bible, MS M. 240, fol. 8, The Morgan Library & Museum

When it comes to defining power, authority, and agency, it can be difficult to settle on one definition. Power is fluid and complex, and when it comes to analysing power exercised by women, it can fall outside of formal areas of the historical record – often found in diplomatic spheres, exercised through influence and mediation. Female power does not always survive in the historical record – such records have been focussed on documenting histories of male elite actors or religious histories after all. But it can be found through the lenses of gender and co-rulership, in part because the king shares at the very least resources if not amounts of power with his queen. It can also be found through these lenses because by examining monarchical pairings we understand better the power of the king through what the queen can share with him – whether that be a dowry, titles, or other types of power.

Much more work needs to be done on co-rulership – it draws from a strong foundation on the work conducted on corporate and composite monarchies, not least from the studies undertaken by Theresa Earenfight and J. H. Elliott. But it also needs to be thought of as a lens and approach to be utilised more often within royal, political, and court studies – even for those who work on the elites, looking at power dynamics both inside and outside the monarchy can tell us far more about the power and rule of a king and his co-rulers, than can be gained by studying a ruler alone. Co-rulership as I hope I have made clear, can also help us understand much more about female power and agency, not only in the medieval world, but before and beyond too.

Bibliography

Storey, Gabrielle. “Co-Rulership, Co-operation, and Competition. Queenship in the Emerging Angevin Domains, 1135-1230.” University of Winchester, PhD thesis, 2020.

Ward, Emily J. Royal Childhood and Child Kingship. Boy Kings in England, Scotland, France and Germany, c. 1050-1262. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2022.

Woodacre, Elena. The Queens Regnant of Navarre. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2014.

Woodacre, Elena. Queens and Queenship. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2020.

Dr Gabrielle ‘Gabby’ Storey is a historian of Angevin queenship, gender, and sexuality. She is writing a forthcoming biography on Berengaria to be published with Routledge in 2023. She has contributed to articles for History Extra and BBC History Revealed, and recently published an open-access article with the Royal Studies Journal (issue 9.1) on homosocial and “homosexual” bonds between the kings of England and France in the twelfth century, alongside chapters on the Angevin queens. She has also edited the collection Memorialising Premodern Monarchs. Medias of Commemoration and Remembrance (Palgrave, 2021).

[1] Elena Woodacre, Queens and Queenship (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2020); Gabrielle Storey, “Co-operation, Co-Rulership and Competition. Queenship in the Emerging Angevin Domains, 1135-1230,” (University of Winchester, PhD Thesis, 2020).

[2] One recent excellent work demonstrating this is Emily J. Ward, Royal Childhood and Child Kingship.Boy Kings in England, Scotland, France and Germany, c. 1050–1262 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2022).

Leave a comment