Cherish Watton.

Think of any topic, and someone, somewhere, has probably made a scrapbook on it. People scrapbooked on things which were important to them; family, friendships, professional activity, popular culture, political, and associational activity. Scrapbooks didn’t just document family life. Politicians and diplomats turned to scrapbooks to record their careers and were often acknowledged within their circles of work. They could be joint endeavours too; made in partnership with family members, friends, or colleagues.

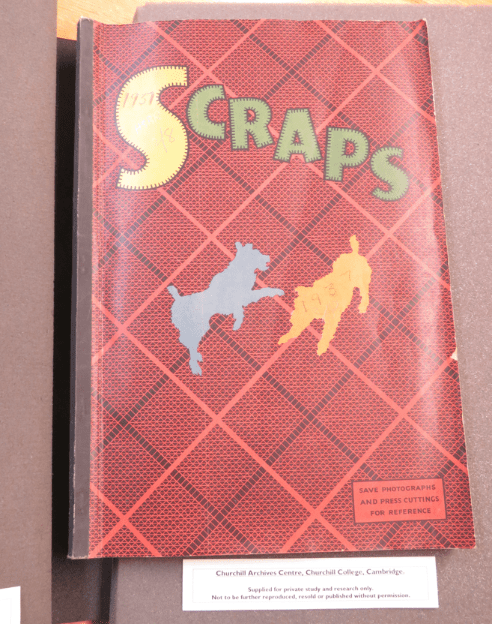

Anyone could make a scrapbook, providing they had scissors, glue, and paper. Victorian Britain witnessed the explosion of scrapbook making as a popular past time. Capitalising on the development of chromolithic technology, companies produced a range of scraps and templates which people could paste within their new scrapbooks. In twentieth century Britain, scrapbookers were able to draw on an abundance of visual material, heralded by the growth in home photography.[1] In the interwar period, stationers such as Woolworths sold loose leaf ring-books, folders and inserts for six pence or less – making them affordable to larger proportions of the population.

Florence Horsbrugh to document her political activity in 1937.

From The Papers of Florence Horsbrugh, HSBR 2/8, 1937.

When the archivist places a scrapbook on your desk, you’re never quite sure what you’re going to find preserved inside. You carefully lift the page, weighed down by the material held on top of it. In what other historical source could you find a newspaper clipping next to a cigarette butt; photographs next to leaves; and letters next to leaflets? Despite the material richness of scrapbooks, few historians appreciate the cultural richness and diversity of these electic, untamed mediums.

This is perhaps because scrapbooks can be difficult to analyse. They were often meant as a conversation piece; showed to family and friends in the home.[2] When they are placed on the desk, we often sorely lack the oral commentary which would bring these volumes to life. However, we shouldn’t use this as an excuse for not engaging with the scrapbooks. For some historical actors, their scrapbook is the only surviving archive material which remains for historians to use to unlock their lives.

We can approach a scrapbook from many angles. First, they are in and of their own right an object, which simultaneously bring together other objects. As Clare Pettitt acknowledges, scrapbooks can become so full of material that they are ‘more “object” than “text”’, presenting a tactile representation of the scrapbooker’s world.[3] Pursuing a material culture approach, we can look at what type of volume the scrapbooker selected: was it a hard-volume bought from a high-end stationers such as John Walker & Co aimed at ‘authors, clergymen, students, lawyers, and All Literary men’ or a paperback Whopper scrapbook readily available at a cheap price?[4] The scrapbooker’s material choices can tell us about the value they gave to their collection. Was it nothing more than a simple past-time or did they have a more deliberate eye to legacy making, in a similar vein to a photograph album or memoir?

Once we’ve taken in these initial material choices, we need to delve deeper and consider the items which have been preserved inside a scrapbook. The blank pages of the scrapbook mean that material can be juxtaposed in unusual ways. How has the scrapbooker decided to arrange material: chronologically, thematically, or does there appear to be no order at all? Is there a connection between different items on a page? Are their certain moments which they’ve chosen to conceal or highlight?

and sent to Adeline to include in her second scrapbook, 1920.

From the Papers of Maurice Hankey, 1st Baron Hankey, HNKY 2/2 November 1917–July 1920.

For example, in Adeline Hankey’s scrapbook on her husband Maurice’s diplomatic career, she pasted a postcard from Maurice to their daughter on the same page as a family photograph published in the society periodical The Tatler in 1921. Notably, this photograph showed the family without Maurice, who was absent on government business. On the surface, this juxtaposition of a postcard and periodical page might seem random. However, Adeline used these items to reunite her family, at least on the pages of her scrapbook.[5]

If you’re lucky enough to have other archival material available, then compare the scrapbooks with other items within the collection. If someone has created multiple scrapbooks (and they often do), are they consistent in their scrapbooking methods? Do they collect more or less material as time goes on and what does this reflect about the time and care they’ve invested in the volumes?

Take Florence Horsbrugh’s scrapbooks for instance. Horsbrugh was one of fifteen female MPs to sit in the House of Commons up until the Second World War. She appeared to keep most, if not every, cutting on her political career for the first few years of her time as Conservative MP for Dundee. However, towards the end of her time in politics she stopped collecting these articles, maybe overwhelmed by their abundance and the time-consuming nature of gluing and labelling each cutting.

These questions should be used as a starting point for engaging with scrapbooks – and will no doubt lead you to ask many more. Scrapbooks are, as Robert DeCandido has described ‘the children of our minds, our hearts, and our egos – frustrating, intriguing and fascinating’.[6] Produced in response to many aspects of private, public, and political life, they quite rightly they deserve more of our historical attention.

If you’d like to find out more about scrapbooks, then check out the following books:

- Bello, Patrizia Di. Women’s Albums and Photography in Victorian England: Ladies, Mothers and Flirts. Aldershot: Routledge, 2007.

- Garvey, Ellen Gruber. Writing with Scissors: American Scrapbooks From The Civil War To The Harlem Renaissance. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012.

- Helfand, Jessica. Scrapbooks: An American History. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2008.

- Tucker, Susan, Katherine Ott, and Patricia P. Buckler, eds. The Scrapbook in American Life. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2006.

Cherish Watton first started at looking at scrapbooks when she was an MPhil student in Modern British History at the University of Cambridge. At Churchill College, she wrote her dissertation on women’s scrapbooks on political and diplomatic activity, from c.1890-1939. When Cherish is not working as Communications Officer for the loneliness and technology charity WaveLength, she runs an award-winning website on the work of the Women’s Land Army. Find her on Twitter at @CherishWatton

[1] Clare Pettitt, ‘Topos, taxonomy and travel in nineteenth-century women’s scrapbooks’, in Travel writing, visual culture and form, 1760-1900, ed. Mary Henes and Brian H. Murray, Palgrave Studies in Nineteenth-Century Writing and Culture (Basingstoke, 2015), p. 28. See also Liz Wells, Photography: A Critical Introduction, 2nd Ed (London, 1997).

[2] Patrizia Di Bello, Women’s Albums and Photography in Victorian England: Ladies, Mothers and Flirts (London, 2007), pp. 16, 47; Ellen Gruber Garvey, Writing with scissors: American scrapbooks from the Civil War to the Harlem Renaissance (Oxford, 2012), p. 118.

[3] Pettitt, ‘Topos, taxonomy and travel in nineteenth-century women’s scrapbooks’, 36.

[4] For example of this John Walker & Co. scrapbook, see Adeline Hankey, Scrapbook relating to Maurice Hankey’s career, Cambridge, Churchill Archives Centre, The Papers of Adeline, Lady Hankey, AHKY 3/1/3, 1903-1920, p. 1.

[5] Churchill Archives Centre, Archives of Lord Hankey of the Chart (Maurice Hankey) (1877-1963), HNKY 2/3, p. 23.

[6] Robert DeCandido, ‘Scrapbooks, the smiling villains’, Conservation Administration News, no. 53 (April 1993): 18–19.

Figures 1. and 2. were provided by the author with permission from the Churchill Archives Centre. For more on the scrapbooks of Adeline Hankey, visit the online exhibition on the Churchill Archives Centre website.

The cover image is in the public domain.

Leave a comment