CIARAN JONES

I recently submitted my PhD thesis on Protestant spirituality in early modern Scotland. Focussing on witchcraft trials, my thesis was mainly concerned with how your average seventeenth-century peasant articulated certain spiritual ideas. Using mostly manuscript records of witchcraft trial confessions as my source base, I compared how these ideas were expressed in different but related contexts, such as ministers’ sermons and educated laypeople’s diaries. Overall, I demonstrated that ordinary parishioners were not excluded from engaging in a particular, evangelical Reformed Protestant culture of piety; a culture, which, until recently, most historians had only discussed in relation to educated and erudite laypeople and clerical figures.

On a broader methodological level, the thesis also implicitly asked whether inner spiritual experiences – such as conversions or communications with God or the Devil in the mind – could be interpreted as forms of spiritual behaviour, with predictable patterns in how specific thoughts, feelings, as well as outer gestures were culturally understood and expressed. To tackle this question, I drew on modern sociological and social psychological ideas of role theory.

Role theory

Sociologists and social psychologists define roles as a set of expectations or scripts tied to a particular position or status that guides people’s attitudes and behaviour. These are not subjective or personal expectations or scripts that a person attaches or associates with a status or position, but rather expectations or scripts governed by wider societies and cultures. An example that is widely cited to explain roles is that of a university student. Tied to the role of a university student are a set of expectations of how an individual who occupies this position should behave. Expectations include, ‘learning new knowledge and skills, establishing an area of study, passing courses, acquiring a degree, and so forth’.[1] We might also say that there are scripts which centre on how one achieves these expectations. For instance, to acquire a degree, a student must attend lectures, write essays and take exams. If a student does not adhere to these scripts and fulfil the expectations attached to this position, then they cannot be considered as genuinely occupying that position; if an individual occupying the role of a student does not submit essays or sit exams, mitigating circumstances notwithstanding, then they are not usually a student for much longer.

Early on in my research I came across a major methodological challenge when thinking about applying this type of theory to early modern Protestant spirituality. Considering sociologists and social psychologists generally define roles as sets of expectations or scripts of behaviour, how, then, do such theorists define and measure behaviour? What follows is a debate about the nature of internal states – the mind, thoughts and feelings – and actions – physical gestures, language, words – and the relationship between the two.

Roles, behaviour, the internal and the external

Modern sociologists and social psychologists generally define behaviour as actions, such as physical gestures and words, which can be observed during social interaction. A general, heuristic definition might read as follows: behaviour is how we conduct ourselves in the presence of others. Now, sociologists and social psychologists argue that our behaviour is influenced by our thoughts and feelings, but because our thoughts and feelings cannot be measured outright – they are hidden and private – then they cannot be categorised as forms of behaviour. How, then, can we apply modern theoretical understandings of role theory and behaviour to an intensely internal topic as Protestant spirituality?

In the context of early modern Protestant spirituality, actions do not matter – everything takes place internally and concerns people’s internal states, their thoughts and feelings in relation to God. In my thesis I make the case, drawing on role theory and the philosopher Charles Taylor’s idea of the ‘porous self’, that the separation between self (mind) and body that we hold today in the Western world was not fully formed in the early modern period.[2] Early modern people were porous, in the sense that both their self (mind) and body could be influenced by supernatural forces to a much greater extent than even nominal Christians would argue today.

An important part of this theory of the porous self is the idea that early modern people’s thoughts and feelings were not private. I argue that much like how our actions during social interaction are used as evidence of behaviour today, early modern people conceptualised their internal states in much the same way: their thoughts and feelings could be seen, observed and even influenced by God and the Devil as historical actors. So, I try to make the case, taking this line of thought, that nowadays what we think of as simply thoughts of the Devil or God, were early modern people’s perceived spiritual experiences of interactingwith the Devil or God in the mind. Therefore, in the context of such internal interactions, early modern people’s thoughts and feelings can be considered as forms of behaviour.

Mistress Rutherford

An example to illustrate this argument: ‘Mistress Rutherford’, a godly woman in early seventeenth-century Edinburgh whose further identity remains unknown. Many conversion narratives, by pious but socially ordinary Scots, explicitly addressed God, the Devil and the Holy Spirit observing or influencing their thoughts and feelings. Rutherford recorded a spiritual experience she had aged fourteen when, whilst she was at prayer, the Devil ‘cast it into my mind, Quhat is that thou is doing? Thou is praying to God; there is no God’.[3] According to Rutherford, the Devil had planted sinful thoughts of unbelief inside her mind.

A question arises here: was Rutherford implying that the Devil made her believe that there was no God, or that she, herself, thoughtthat that there was no God, and that she attributed this to the work of the Devil when writing this narrative in her diary? Admittedly, most historians and literary scholars would refer to the latter to explain such narratives, since most scholars do not usually refer to God and the Devil as historical actors. But this type of explanation devalues the idea that for people living in societies where God and the Devil and other supernatural entities were not simply held to be real, but were understood to be and described as tangible historical actors, the recording of supernatural encounters should be seen, in part, as conforming to a dominant spiritual culture and not just the product of translating personal experience onto the page, or reducing such narratives as creative use of metaphorical language. Though she wrote that she had a thought of unbelief, Mistress Rutherford attributed them to the work of the Devil influencing her. In making this type of statement in which a supernatural entity was held responsible for influencing her thoughts and feelings, Mistress Rutherford described the Devil as an historical actor who interacted with her internally, and hence she described her mind as an environment for spiritual confrontation. And Mistress Rutherford’s experience was not unique. Many other pious but socially ordinary Scots described similar experiences of interacting with the Devil and other supernatural entities in these ways. These types of sources are incredibly intimate – they are about personal faith and one’s perceived lived experiences translated onto the page. The historian is quite rightly tempted to view these as subjective, but when taken together and compared with each other, these personal sources demonstrate an adherence to a widespread spiritual culture which expected all Scots, of all social ranks, to categorise their spiritual identities according to predefined and culturally accepted behaviours and expectations. Through using these personal sources and modern role theory, the historian can see what types of behaviours and identities mattered to early modern Scottish society.

Ciaran Jones recently submitted his PhD in Scottish History at the University of Edinburgh. His thesis was on the topic of Reformed Protestant spirituality in early modern Scotland, with a particular focus on the witch trials. Ciaran recently produced a scholarly edition of a newly discovered witchcraft source, published in the latest volume of the Miscellany of the Scottish History Society. You can find Ciaran on Twitter as @Ciaran_Jonesy, and as a regular guest on BBC Radio Scotland’s Time Travels and Witch Hunt.

[1] Peter J. Burke and Jan E. Stets, Identity Theory (New York, NY, 2009), 114.

[2] Charles Taylor, A Secular Age (Cambridge, MA, 2007), 27-42, at 38.

[3] ‘Mistress Rutherford’s Conversion Narrative’, ed. David George Mullan, in Miscellany of the Scottish History Society, XIII (Scottish History Society, 2004), 146-189, at 152-3

Figure 1. William Holl, ‘John Knox’ (c.1860). Held by the National Library of Wales and available in the public domain.

Figure 2. Detail from A History of Witches (c.1720). Available via the Wellcome Collection and available in the public domain.

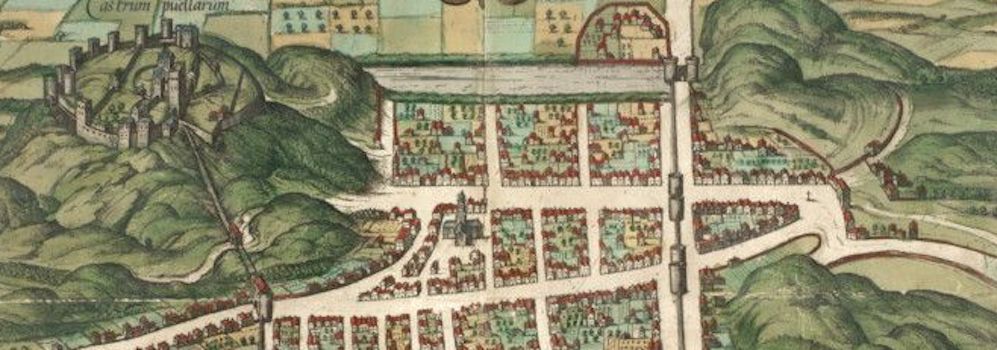

Header image. Franz Hogenberg, ‘Birds Eye View of Edinburgh’ (1582). Available via the National Library of Scotland and believed to be in the public domain.

Leave a comment