DR SAMIRA SARAMO

At the turn of the twentieth century, Finnish migrants, drawn by the familiar landscape of lakes, forests, and rocky outcrop, settled in the rugged wilderness of Northern Ontario in Canada and overcame the harsh conditions of the early years through their inherent Finnish characteristic of “sisu” (determination, perseverance, guts)… or so the story is most often told. Through the stories we tell, we build our connections to communities, places, and pasts. But what might happen if we shift and reframe the ways we tell and view foundational narratives?

I’ve been researching Finnish migrant histories in Canada and the United States for about fifteen years and I am particularly drawn to personal narratives and life writing (especially letters and autobiographies) that offer us glimpses of everyday life and the fluid workings of people making sense of themselves, their relationships, and their worlds. Over recent years, I have turned more frequently to analyzing how Finnish migrants have narrated encountering and feeling natural landscapes.

In part, I have been compelled by a curiosity to understand the often repeated and mostly taken for granted notion that Finns have a unique relationship and affinity with nature. I am further driven to explore how and why places are made and re-made emotionally, socially, and physically. As I delve more deeply into Finnish migrant narratives of place and belonging, I have become increasingly aware of the ways that, through their telling, other histories and presences are obscured.

The Canadian nation state has been built and legitimized through ongoing violences against First Nations, Métis, and Inuit people. Differing in form and practice from extractive colonial endeavours, settler colonial projects, such as those established in Canada, the United States, Australia, and Aotearoa (New Zealand), aim to erase and replace to build a new state in the image of the colonizer.[1] The making of Canada depended on Indigenous dispossession so that the ‘empty’ ‘wilderness’ could be ‘tamed’ by re/creating spaces, populations, institutions, and practices. As a structure made “by people rather than by empires,” migrants have been the key to settler colonialism.[2]

The histories of Finnish migrant communities, families, and individuals are conspicuously silent on Finns as settlers and on encounters with Indigenous peoples or places. Instead, Finnish migrant life writing and community narratives most often follow what Lorenzo Veracini has noted as the “typically settler narrative of adaptation, struggle against a harsh environment, economic development, and integration.”[3] Finns are not alone in practicing such silences.

The experiences of, in the Canadian case, non-Anglo and non-Francophone migrant groups have long been cast as outsider histories. The struggles of carving a place in the dominant culture have left little room for considering “migrant settlerhood.”[4] Historians have also perpetuated this erasure. Laura Madokoro has thoughtfully called out the ongoing disconnect between migration history and settler colonial studies and emphasized the urgency of bridging this gap.[5]

It is difficult to shake the stories we have told ourselves and about ourselves for generations. Yet, if we continue to leave our ‘settlerhood’ unexamined, we risk continuing to harm the Indigenous people on whose land and at whose expense we have built our lives and histories. The challenge before us, then, is how to begin to reframe our histories in ways that make space for all that has been made invisible through omission.

What might such a history of Finnish settlement look, sound, and feel like? How can I, as a scholar and as a member of the community whose histories I write, help facilitate such a re-envisioning?

As of September 2020, I now have the opportunity to jump into these questions. With thanks to the Kone Foundation, over the next four years I will develop a multilayered and multisensory digital map of Ontario to push entrenched assumptions about Finnish history in North America. This deep map will allow cartography, narratives, photographs, soundscapes, demographic statistics, ecological description, and archival documents to be layered in different ways in the hope of offering new ways of seeing complicated and overlapping claims on place, belonging, and history.

Through this approach and tool, Finnish migrant histories will not only be situated in the community’s own significant sociocultural and everyday places, but also spanning over time in the changing contexts of the physical environment, Indigenous place-views, state-imposed colonial frameworks, and overviews of historical population and economic data. While there is a lot of work ahead to see the map to full realization, this is also an exploration of process.

I am excited to contribute to the humanist aspiration of deep mapping to reflexively provide multifaceted, multisensory, and transdisciplinary spatial narratives that can enrich traditional (and arguably limiting) academic written narratives.[6]This project is pushing me as a scholar to think and communicate in ways I have not before and to utilize (Historical) GIS tools and methodologies that are new to me. It also allows me to respectfully engage the communities my research studies and serves in new dialogue that makes space for discomfort.

This process is also important to me personally, as a continuation of confronting my place, complicity, and privilege in Canadian settler colonialism. As historians, we are rarely convinced of the uniqueness of particular events or – as we have heard repeatedly in 2020 – of “unprecedented times” because we understand historical paths and continuities. By making historical Finnish migrant participation in the processes of settler colonialism and Indigenous displacement visible, I hope it becomes easier to see how Finnish migrant communities have a role to play now, too, in identifying, making visible, and dismantling the structures that uphold colonial power in Canada today.

Dr. Samira Saramo, Senior Researcher at the Migration Institute of Finland, is a transdisciplinary historian of migration, place-making, and the everyday, whose work centers on Finnish migrant communities. You can connect with Samira on Twitter: @samira_saramo.

[1] For settler colonialism as a concept, see Lorenzo Veracini, Settler Colonialism: A Theoretical Overview (Palgrave Macmillan, 2010).

[2] Adam J. Barker, “Locating Settler Colonialism,” Journal of Colonialism & Colonial History 13, 3, (Winter 2012), 4.

[3] Lorenzo Veracini, “The Imagined Geographies of Settler Colonialism,” in Making Settler Colonial Space: Perspectives on race, place and identity, Tracey Banivanua Mar and Penelope Edmonds, eds. (Palgrave MacMillan, 2010), 187.

[4] Laura Madokoro, “On future directions: Temporalities and permanency in the study of migration and settler colonialism in Canada,” History Compass 17 (2019), 2. https://doi.org/10.1111/hic3.12515

[5] Laura Madokoro, “Peril and Possibility: A contemplation of the current state of migration history and settler colonial studies in Canada,” History Compass 17 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1111/hic3.1251

[6] See for example David J. Bodenhamer, John Corrigan, and Trevor M. Harris eds., Deep Maps and Spatial Narratives(Indiana University Press, 2015).

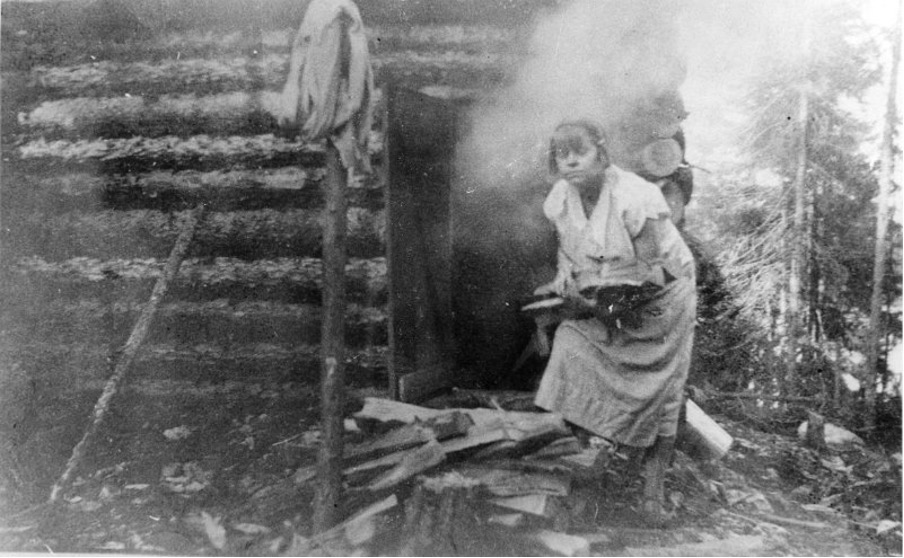

Image 1: Heating up the sauna at a lumber camp in Sault Sainte Marie, Ontario, circa 1930. Varpu Lindström Collection/Migration Institute of Finland Archives, KAN 0100. Image provided by the author with gracious permission from the Migration Institute of Finland Archives. Public re-use is not permitted.

Image 2 (and banner image): Finnish Homestead, 1908. Varpu Lindström Collection/Migration Institute of Finland Archives, KAN 0202. Image provided by the author with gracious permission from the Migration Institute of Finland Archives. Public re-use is not permitted.

Leave a comment