By Rachel Smith

Whilst reading through the eighteenth-century Canning Family archive at the West Yorkshire Archive Service in Leeds, I came across a rather interesting letter from John Murray, a publisher, to a Mrs Butler. Dated 25th July 1912, he wrote that

I gather from what Miss Routh and Mr. Duff told me that the materials in your possession deal mainly with the early days of the Canning family, and the youth of George and Stratford. If a complete and coherent work on this period and subject could be produced and kept within the limits of one moderate sized volume, I think it might meet with a good reception.[1]

However, once he read the early manuscript for the project in 1913, he stated that

a good many of the letters in this [sic] chapters are not of marked literary or historical significance: the characteristics of the writers might be brought to a reader equally well if they were edited judiciously…there is a great deal of that kind of material on the 18th century already in print (e.g. Seasons at Bath) and there is probably in family archives plenty more that would not justify publication…the central figures must be George and Stratford Canning, and in order to bring out this purpose care must be taken not to overload them with collateral detail.[2]

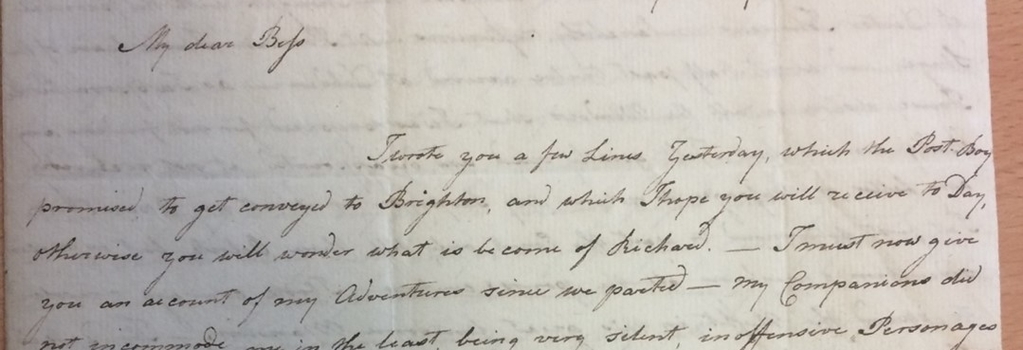

The collateral detail mentioned by Murray were the letters of Mehitabel ‘Hitty’ Canning and Elizabeth ‘Bess’ Canning, politician George Canning’s aunt and cousin respectively. Their eighteenth-century letters are the backbone of the defunct manuscript and they presented Mehitabel as the central connection between all the family members of the Canning family. Although Murray acknowledged that Mehitabel and Elizabeth’s letters, especially the ones to each other, were ‘very clever’, Murray’s response clearly depicts his belief that a book focusing on these unknown female protagonists would not sell, and that it was their famous relatives, George and Stratford Canning, that would be the major pull.

Murray’s comments reflect the general status of women’s history in the 1910s.[3] June Hannam noted that women were just starting to write their own histories at this time, after finding that women were largely absent from historical texts, an initiative that did not really develop until the 1960s. Moreover, Murray was writing at a time of female political unrest: the Suffragettes had become more militant at a time where women were still expected to remain at home as wives and mothers. Therefore, a manuscript full of letters by women was not reflective of historical interest at that time. Now, women’s history is a burgeoning field, with a rich variety of research strands including the histories of motherhood, women’s politics, and women’s social history.[4]

These letters between Mehitabel Canning and her daughter, Bess, are about the everyday, the routines, the seemingly mundane details of life in the eighteenth century. Yet it is through their everyday conversations that a picture of the intimate relationship between a mother and daughter emerges. Individuals lived their lives through everyday encounters and relationships and this correspondence epitomises the nuances that we can learn from their letters.

The importance of the letters as a tool of communication is evident, both for practical and emotional reasons. A role of the sentimental mother was to educate her children, especially her daughters, and their correspondence allowed Hitty to continue this duty whilst she or her daughter were away from home, sometimes in a manner similar to distance learning today. As well as teaching her about letter writing itself, Hitty’s letters aimed to help Bess improve her French, her knowledge of society and household management.

These letters also taught skills such as discipline and self-awareness, traits which Bess inherently displays throughout her adult letter writing. These tools were essential for entering polite, elite society, with whom the Canning family socialised, as they allowed one to correct any faults with diligence, become masterful in accomplishments, display a natural modesty, and eventually ensnare a husband. Hitty was essentially parenting through her correspondence, an aspect which has not been fully analysed and is important for understanding eighteenth-century parenting.

The correspondence also reveals information on how the postal service fit in with their daily lives, giving another glimpse into eighteenth-century life. The postal service dictated letter writing to some extent. Deemed to be worth using up precious paper and ever-growing postal costs, news of the postal service’s timings, speeds and ‘quirks’ filled up space in most letters. That this deserved such attention from eighteenth-century letter writers is important as it shows the emotional importance of letters to their recipients, a subject worthy of more attention.

Moreover, the postal service’s daily timings, which often resulted in hastily scribbled closures to letters, are mentioned throughout the correspondence, as well as how they were delivered, how much they cost and the speed of travel to certain places. Thus, the letters are also evidence of the working post office and one can learn about how it operated, valuable evidence to the study of the eighteenth-century postal system.

The content of the letters, though often instructing Bess, also reveal Hitty’s influence as a parent and Bess’s intellectual and social development. The discussions surrounding housekeeping give an insight into the roles of servants in the household, differentiating tasks between different types of servants and the mistress of the house and how Hitty was able to run the household through her correspondence with Bess.

Yet Hitty’s influence over her daughter is seen most keenly through their discussion of politics. One sees Bess’s sharp political awareness when she was only thirteen and her similar views and behaviour towards Hitty, eager to please. Only an intimate correspondence such as this would reveal a mother discussing politics with her child so openly and the political impact on the child seen so clearly. This led to Bess gaining knowledge of other worldly matters and the letters reveal all sorts of anecdotes and details of larger historical events and famous figures from the time, allowing historians to better understand how these events shaped everyday lives and build a larger picture of what life was like in the eighteenth-century.

Hitty and Bess’s correspondence is full of historical significance and with the development of gender history, the history of emotions, and the changes in views towards women since the letters were last considered for publication, one can finally see their merit as rich historical sources deserving attention. Though Murray was not necessarily incorrect in stating that they would not meet with a good reception unless George and Stratford Canning were the focus one hundred years ago, this blog, and indeed my forthcoming article in History, proves that they are certainty able to hold their own now.

Rachel Bynoth is a final year PhD student based at Bath Spa University and Cardiff University, funded by the South, West and Wales Doctoral Training Partnership. Her doctoral research examines expressions of anxiety within remote relationships across the lifecycle, through a case study of the Canning Family letter network, 1760-1830. Her research interests include social, gender, political and emotional histories between 1700-1945. She is History Lab Seminar Co-Convenor and co-organiser of the Distant Communications project.

Twitter: @Smudge2492

Website: https://rachelabynoth.wixsite.com/misshistorian

[1] Elizabeth Canning to Mehitabel Canning, 6th December 1798

[1] John Murray to Mrs Butler, 25th July 1912

[2] John Murray to Mrs Butler, 1913

[3] There were very few female historians at this time, the most famous of which is arguably Alice Clark.

[4] See Hannah Barker and Elaine Chalus ed., Women’s History: Britain 1700-1850, An Introduction, (London, 2005), p.1-5

All images are author’s own and not to be re-used without permission.

Cover Image. Letter from Mehitabel to her daughter, Bess, 13th February 1789, WY888, West Yorkshire Archives, Leeds, taken by Rachel Bynoth (2017).

Figure 1. Mehitabel Canning with her daughter, Bess, Fyvie Castle, taken by Rachel Bynoth (2019).

Leave a comment