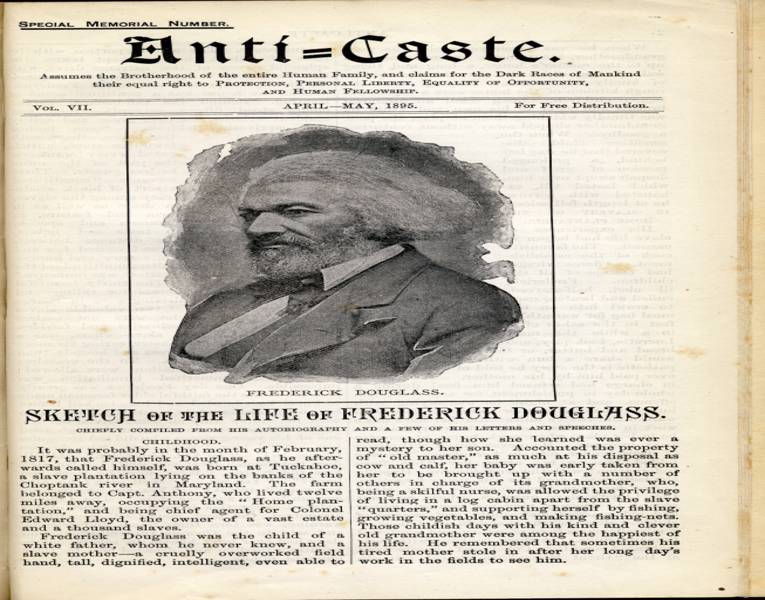

Figure 1: Sketch of the life of Frederick Douglass in Special Memorial Murder (1895)

By Becky Taylor

Black History Month is often a time when I reflect not only on how Black British histories inform my own research on histories of marginalised and racialised groups – Gypsies and Travellers, refugees, the vilified poor and migrant populations – but also on the leading role Black historians and historians of Colour have had in shaping our – and my – understanding of those histories.

Last year had me reading History Workshop Journal’s inspiring ‘virtual special issue’ that saw a group of its editors exploring the history of Black British history and drawing together over twenty key scholarly articles, reflections and blog posts to reflect on how scholarship has developed and changed our understanding of Black histories over the past five decades.

This year, moving from this macro-level thinking to what at first looks like the micro-level I have been revisiting Caroline Bressey’s work on Anti-Caste, a small magazine first published in England by the English Quaker and activist Catherine Impey. Never exceeding a circulation of 7,000, and edited from her home in Street, Somerset, this largely-forgotten publication could be written off as a parochial, marginal story of nineteenth-century humanitarian endeavour.

And yet Bressey shows us how this radical magazine sought to analyse and re-imagine ‘race’ across the English-speaking world. From its founding in March 1888 to its folding in 1895 it worked to expose and understand and push against the ‘Colour Line’ that it argued was being actively constructed in the United States and across India and the ‘settler colonies’ of the British Empire in the second half of the nineteenth century. In the process it developed what we can think of as a robust and radical anti-racist critique of the divisions that were produced and actively sustained by capitalism and empire.

Crucial to her project was Impey’s mobilisation of a counter-network that she intended would unite ‘people of any country blacks + whites + Indians Africans Americans Europeans all in one roll’ to resist racial segregation. Her insistence on cross-racial solidarity set her apart from similar reforming and campaigning organisations and journals, such as the Anti-Slavery Society. By rejecting the idea of ‘speaking for’ oppressed peoples, and instead by actively recruiting ‘people of colour’ to contribute to the magazine, and putting their words alongside white writers, Impey produced a space that challenged conventional interpretations of international race relations. And, as Bressey points out, in actively listing ‘races’ -‘No matter what colour people are – yellow, brown, black, olive, white – all of them are just men and women like ourselves’ – she also sought to make visible ‘whiteness’ as a racialised identity, not outside of race but simply one among others.

This then is no micro-study at all. Not only does it feel startlingly relevant for today, but it offers an insight into a globalised intellectual movement that concerned itself with lynching and the everyday experiences of Afro-Americans as much as it did the oppression of tea-pickers in Assam and Australia’s Aboriginal peoples. In doing so Impey believed it was essential to make analytical connections between these apparently unrelated phenomena. Throughout the publication’s lifespan it also, as with scholars and activists today, grappled with the challenges of finding a language with which to discuss race without reinforcing its divisions.

For me, as a historian, illuminating this movement and historical moment from which it emerged allows me to think more richly and deeply about the movement of peoples and ideas and the cross-cutting currents of the late nineteenth century. It shows how histories that make connections across places – Somerset, the American South, the Indian Raj, Australia – and between people – Irish, British, Indian, American, Aboriginal – offer us more nuanced accounts of the past.

And finally, even today there is a tendency to locate both ‘race’, and thinking about race as a metropolitan concern and project, both alien and irrelevant to rural Britain. But in it locating Street – a small town in Somerset, these days still most often associated with Clarkes shoes – as one of the centres of a global network of activists and thinkers, Bressey firmly reminds us that ‘race’ has long-been as present in provincial and rural areas as it has been in Britain’s more visible urban cores.

Becky Taylor is Professor of Modern History at the University of East Anglia where her research explores the relationship between minority and marginalised populations and the state.

Leave a comment