DR HANNAH TELLING

What is gender history and why does it matter? For me, it is a discipline that provides a fascinating insight into the often-overlooked aspects of history. I was first introduced to gender history as an undergraduate and the University of Edinburgh, when I enrolled on a course called ‘Gender and Sexuality in Early Modern Europe’. The set reading for the first week was Katherine Park’s 1997 article, ‘The Rediscovery of the Clitoris: French Medicine and the Tribade, 1570-1620’. I was introduced not only to early modern ideas of medicine and sexual difference, but also notions of male privilege and authority, female sexuality and the ‘deviant’, transgressive female body. This was the type of history that I wanted to read, to research – and to contribute to.

My research interests have shifted temporally since that seminar in 2011. I am now a historian of violence, law and crime during the nineteenth century. Yet, I am still very much a gender historian and so I was excited to help build an innovative and ambitious new course entitled ‘A Global History of Sex and Gender: Bodies and Power in the Modern World’. This four-week, open-access MOOC (Massive Open Online Course) launches on FutureLearn on 26 October and aims to introduce learners to gender history as an approach that has the potential to sharpen and transform our understanding of the past.

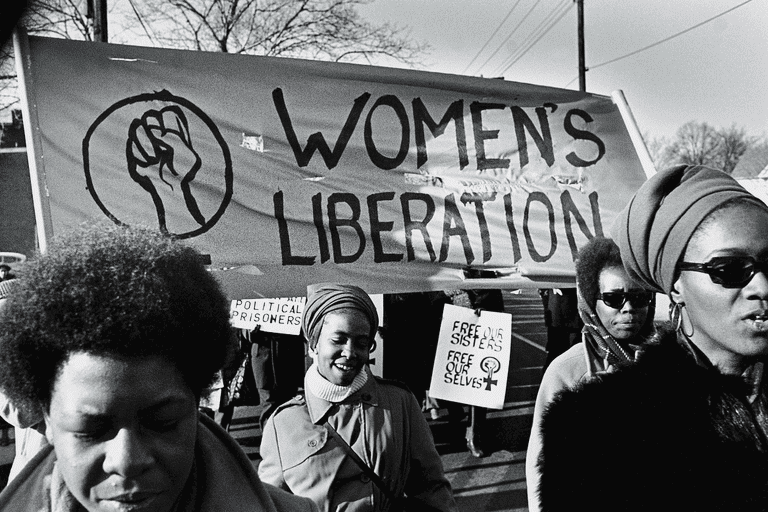

As a discipline, gender history has its roots in second-wave feminism. Prior to the 1970s, historical scholarship was predominantly white, male and Western – though often without the introspection required to recognise that. Feminist historians began to investigate the lives of women in the past, yet quickly recognised that it was not enough to simply ‘add women and stir’. A focus on women in the past disrupted the familiar categories upon which the historical discipline was organised and structured, thereby challenging established historical narratives.

Gender history was not simply an exercise in reclaiming the voices of the marginalised and silenced, though this remains a vital strand within the discipline. As Merry Wiesner-Hanks argues in Gender in History (2001), ‘viewing the male experience as universal had not only hidden women’s history, but it had also prevented analysis of men’s experience as those of men’. Gender history is best understood, therefore, as an analytical approach that applies categories of gender sexuality to the past. Gender culture, the operation of power and how gendered power intersects with other social identifiers, such as race, class sexuality, disability and age, and the symbolic use of gender to signify relations of power. The result is that almost any aspect of history can be transformed and enriched by the adoption of gender as a category of analysis.

Yet, gender history still struggles to be granted the same degree of legitimacy and recognition afforded to other historical sub-disciplines. I vividly remember a research seminar where world-leading gender historians discussed whether leaving the word ‘gender’ out of undergraduate course titles may be the only effective way to address the gender imbalance of courses that remain overwhelmingly female-dominated. Gender history is still all too readily dismissed simply as the history of those on the margins, rather than what it really is: an analytical approach that seeks to uncover more inclusive, representative and relevant historical accounts. To refashion the Italian philosopher, Benedetto Croce’s famous statement: all history is gender history.

It is within this context that ‘A Global History of Sex and Gender: Bodies and Power in the Modern World’ is – to me – so valuable and necessary. By adopting a feminist pedagogy, the content within this course is not just knowledge for knowledge’s sake, but instead provides learners with the skills and tools to think critically about how gender shapes society, both in the past and today. The course is the brainchild of Dr Tanya Cheadle, Lecturer in Gender History. Tanya, myself and Dr Maud Bracke, Reader in Modern History, embarked upon creating a course that drew upon the wide-ranging expertise of staff at the University of Glasgow’s Centre for Gender History, home to the largest concentration of gender historians in Britain. The interdisciplinary teaching team includes over thirty contributors from universities across the world, the Smithsonian Institution and Glasgow Women’s Library.

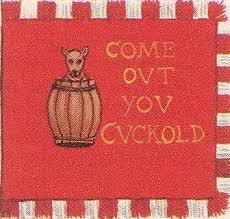

The course is structured in a way that provides learners with an understanding of key theoretical concepts used in gendered analyses of the past, opportunities to gain knowledge and of historical events and the chance to engage with primary sources that have been analysed through a gendered lens – as well as the means to identify and describe the historical contexts that underpin our modern societies. Introducing learners to theoretical concepts, such as patriarchal and heteronormative power structures and cultural constructions of masculinities and sexualities provides the means to reinterpret and reassess historical events. Understanding, for example, constructions of masculinities and patriarchal power in the early modern period adds necessary nuance and contextualisation to flag used the English Civil War. The term ‘cuckold’ refers to the husband of an adulterous wife; thereby providing the insight into the intersections between ideas of gender with warfare and politics.

referring to the Earl of Essex’s notorious martial problems’ (1640s)

The case-studies provided by course contributors show gender in action throughout the past, from the historical provision of care and women’s paid and unpaid work, to the regulation of our bodies and desires throughout history, and the struggles and successes of the feminist challenge. Learners are presented, therefore, with a broad insight into gender history as an applied analytical approach that will provide people of all academic backgrounds with the means to reflect introspectively on their own understanding of the past.

One aim of the course is to facilitate the identification of the patterns of the past that echo in our current societies. Reference to modern societal issues – such as #MeToo, campaigns for women’s and LGBTQ+ rights, and equal pay – serve both as a method for engagement and also as an introduction to gender issues within historical contexts. The course is not just designed for those interested in gender and sexual history. Rather, it is intended for a much broader audience (at any level of study, interest, or expertise) who wish to learn the skills to explore how past events and societies have been shaped by ideas of gender in ways that are still undoubtedly relevant today. Recognising the intrinsic relevance of gender to modern social movements and contemporary issues further underscores the imperative need for historians – and those interested in history more broadly – to engage with and understand the centrality of gender embedded within similar issues in the past. This innovative, ambitious, and truly exciting course aims to introduce participants to new perspectives one the past and show exactly why gender history matters.

Dr Hannah Telling is the Economic History Society Power Fellow at the Institute of Historical Research. Hannah’s research explores gender, violence, society and law during the long nineteenth century. Her current research project is entitled ‘Criminal types: Violence, law and society in Scotland, 1850-1914’ and explores how constructions of criminality intersected with ideas about gender, class, ethnicity and status in nineteenth-century Scotland. The project also explores how this influenced the judicial treatment of violent male and female offenders brought before the courts.

Header Image. Warren K. Leffler, ‘Women’s Liberation March’ (1970). Held by the United States’ Library of Congress and available online under Creative Commons license.

Figure 1. Unknown photographer, ‘Men and women cross-dressing at a party’ (n.d.). Available online under Creative Commons license.

Figure 2. Linda Napikoski, ‘Women’s liberation movement’ (1960s). Available online under Creative Commons license.

Figure 3. Unknown creator, ”A flag used in the English Civil War referring to the Earl of Essex’s notorious martial problems’ (1640s). Available online within the public domain.

Leave a comment